The Medical Minute: Warming winter's chill can be toxic

When winter gets so cold for so long – as it has this year — it can be tempting to look for creative ways to heat things up.

Whether that means bringing kerosene heaters indoors, grilling dinner on a camp stove in the kitchen when the power is out, or warming up the car inside the garage, sometimes creativity can lead to illness, even death.

Carbon monoxide poisoning is the most common cause of death by toxin. It is the reason for about 40,000 emergency department visits and nearly 6,000 deaths each year – most during the winter months, as people use improperly vented devices that burn fossil fuels to keep warm or to cook their dinner.

Carbon monoxide, or CO, is a colorless, odorless and tasteless gas that causes no harm at small levels. The gas joins with the hemoglobin in red blood cells, preventing them from carrying oxygen throughout the body.

Dr. Glenn Geeting, an emergency medicine specialist at Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, said most nonsmokers have less than 3 percent of their hemoglobin joined with CO. (Smokers may find up to 10 to 15 percent of their hemoglobin affected.)

Carbon monoxide poisoning occurs when a higher percentage of the hemoglobin in the red blood cells is combined with CO, essentially starving the body for oxygen. That can result in injury to tissues, especially the heart and brain.

Yet because the symptoms of CO poisoning are very similar to other winter ailments and viruses – headache, fatigue, nausea, general malaise – it can be hard to detect. The only way to know for sure is to do a blood test on those who have been exposed to poorly vented heating devices or structure fires.

Even the pulse oximeters that healthcare professionals clip on a patient's finger to measure the level of oxygen in the blood can be misleading because they don't detect the gas and can be artificially reassuring.

Pregnant women are especially at risk for the condition because a fetus's hemoglobin grabs hold of CO faster than an adult's blood.

“A pregnant woman could have only mild symptoms, yet the baby could be really suffering,” Geeting said.

Those with underlying heart or lung conditions may also be affected more easily. Geeting said treatment usually involves breathing oxygen for a period of time. In more serious cases, hyperbaric oxygen therapy – breathing 100 percent oxygen under increased atmospheric pressure — is used.

Geeting said the easiest way to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning is to be aware of your exposure to items that may be burning a fossil fuel in an enclosed space. While cracking a window or providing other ventilation may be helpful, the best precaution is not to use such devices indoors. Most home heating systems and fireplaces aren't the culprits, he said. It's the other things people bring indoors.

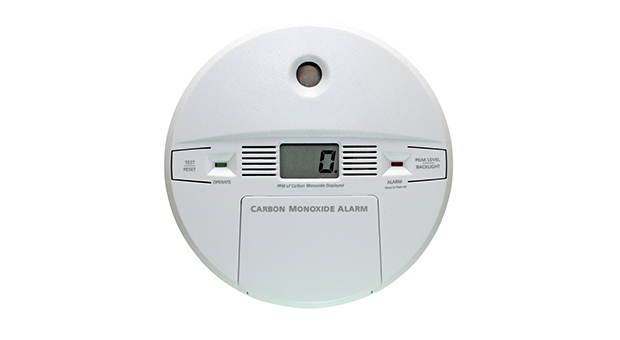

A carbon monoxide detector, which can be purchased at most hardware stores, can alert people to unsafe levels of CO the same way a smoke alarm does for smoke and fire.

To learn more about how to prevent CO poisoning, visit www.cdc.gov/co/faqs.htm

The Medical Minute is a weekly health news feature brought to you by Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Articles feature the expertise of Penn State Hershey faculty physicians and staff, and are designed to offer timely, relevant health information of interest to a broad audience.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.