Cancer cell subpopulation cooperation can grow tumors

Subpopulations of breast cancer cells sometimes cooperate to aid tumor growth, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers, who believe that understanding the relationship between cancer subpopulations could lead to new targets for cancer treatment.

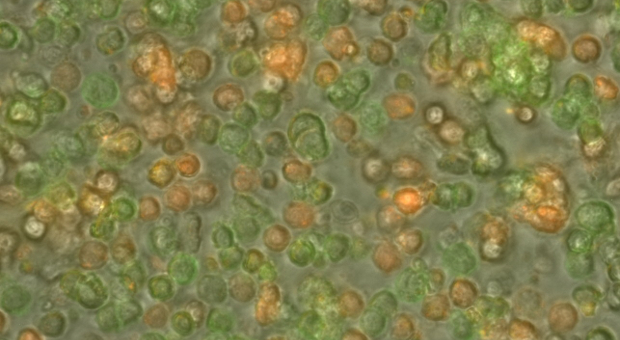

Cancers contain genetically different subpopulations of cells, called subclones. Researchers have long known that these mutant subclones aggressively compete with one another to become the dominant tumor cell population. However, in some cases it seems that no single subclone can achieve dominance on its own.

“In breast cancer, there is remarkable genetic diversity within each cancer, and sometimes that diversity appears remarkably stable,” said Ed Gunther, associate professor of medicine. “No single subclone seems to be capable of gaining the upper hand, leading us to wonder whether subclones might be working together in some instances. Cooperation between subclones could provide a stabilizing force that preserves tumor cell diversity.”

The researchers studied mammary tumors in mice caused by the over production of a protein called Wnt1, which is secreted by tumor cells and is needed to advance tumor growth. They report their results in the current issue of Nature.

The mammary tumors frequently contained two distinct subclones – one produced Wnt1 while the other did not. The researchers observed a co-dependency of the two subpopulations. Instead of competing, the two relied on each other to expand both populations together.

The subpopulation that failed to produce Wnt1 contributed to tumor growth with a mutation in a gene called HRas, which regulates cell division. The subpopulation that produced Wnt1 did not have this HRas mutation.

“One cell type signals to the other,” Gunther said. “When one cell type produced Wnt1, which we know the tumor depends on, the other type sensed it.”

When the researchers prevented the signaling between cells, the cancer growth stopped. However, the longer the messaging between the cells stops, the chance that the cells will adapt increases.

“When we blocked the signaling, the cells got around it,” Gunther said. “Either the cells evolved to find a way to communicate with each other again, or they evolved to not need the cooperation any longer.”

Research could lead to effective ways to block communication between the cells to prevent the cooperation, and slow cancer growth. In addition, understanding the genetic differences between the subpopulations could lead to novel treatment strategies aimed at eliminating tumor cell communities.

Other researchers are Allison S. Cleary, M.D./Ph.D. program student; Travis L. Leonard and Shelley A. Gestl, research technicians, all of Jake Gittlen Laboratories for Cancer Research at Penn State College of Medicine.

The National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, the Pennsylvania Department of Health Tobacco CURE fund and the Mary Kay Foundation funded this research. (R01CA152222)

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.