Peace amid chaos… how spirituality, religion may help families cope

Gina Brelsford was like any other new professor – she hoped she wouldn’t embarrass herself in front of her students. As a new instructor in clinical psychology at Penn State Harrisburg and a soon-to-be mother, she was nervous for many reasons.

“I used to joke with my class that the worst thing that could happen was that I would go into labor during lecture,” Brelsford said.

Her worst-case scenario became reality after just 30 weeks of pregnancy. Without warning, while teaching in 2007, Brelsford began to experience some bleeding and a drop in blood pressure that resulted in an ambulance trip to Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center.

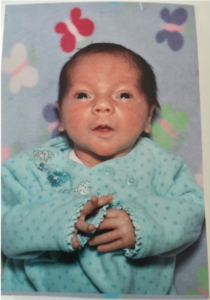

After being sent home that first day, she returned two weeks later and gave birth to a baby girl, Elise, who was taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) just moments after delivery.

“That was an impactful moment for me,” Brelsford said. “I had just given birth to my first child and didn’t see her until the following day.”

Although Elise had no major medical issues, the challenge of being a family during her five-week stay in the hospital was stressful for Brelsford and her husband, Matt. They visited once or twice a day in shifts, while trying to carry on with the routines of daily life.

Brelsford recalled that the NICU nurses and physicians they encountered were supportive, yet she experienced a need for greater psychological and spiritual care and saw it as an opportunity. Previously, she studied how religion and spirituality related to family functioning and emotional well-being. She decided to change course in her research to investigate how support for NICU families could be improved.

Brelsford partnered with Kim Doheny, director of clinical research for the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, to understand how religion and spirituality can play a role in caring for NICU families.

“A stay in the neonatal intensive care unit is a highly stressful experience, even for families with the healthiest babies,” Doheny said. “It’s typically unexpected and traumatic because they’re dealing with the loss of a pregnancy with normal outcomes.”

Doheny and Brelsford published data from their pilot study in the Journal of Psychology and Theology that examined how religion and spirituality contribute to a parent’s ability to experience personal growth following their baby’s stay in the NICU – called post-traumatic growth.

While none of the 25 participants experienced clinically significant levels of anxiety or depression, the data collected four to six weeks after discharge indicated that increased religious coping, spiritual disclosure and sanctification of the parent-child relationship were associated with increased personal growth after the child was discharged from the hospital.

Prayer is an example of religious coping that parents in the study may have used – something Brelsford did a lot of while Elise was hospitalized. Through her prayers for her daughter’s health, Brelsford found some peace in a chaotic situation.

According to the researchers, spiritual disclosure ― sharing views on religious beliefs and faith journeys with a partner ― is another NICU coping strategy. Brelsford and her husband talked often and openly about their faith while Elise was hospitalized.

“He would say things that encouraged me,” Brelsford said. “My faith and the support of my husband brought me out on the other end of the trauma.”

Although parents face many stressors in the NICU environment, the study findings suggest that increased infusing of the parent-child relationship with spiritual significance is related to growth despite the stress from these barriers. Some parents may feel that God is present in their relationship with their child or that their role as parent has spiritual significance.

Brelsford pointed out that even parents without religious beliefs can sanctify their parent-child relationship. Nonreligious parents may feel that the relationship with their child and their role as parent have ultimate value and purpose.

Rose Baer, a chaplain resident in Hershey Medical Center’s NICU, said that naming is one way that many parents sanctify their parent-child relationship. New parents will often name children after relatives or choose names with special meaning.

Baer feels that her role as a chaplain is about being present for families experiencing the ups and downs of a journey through the NICU.

“Spirituality is all about connection,” Baer said. “When there’s connection, there is the possibility of healing and growth.”

Doheny said that since Brelsford’s stay in the NICU more than a decade ago, Hershey Medical Center began offering new resources to help families cope while their baby is being treated. Social workers and child life specialists work together with chaplains to ensure that parents and siblings receive optimal psychological, social and spiritual support during their stay.

Ultimately, Doheny said it takes a team effort to ensure families have the best possible experience in the NICU – and it starts by educating families and checking in with their needs, not just their baby’s.

“We have family conferences after a baby is admitted to the NICU so we can educate parents about his or her condition,” Doheny said. “We tell them what the treatment plan will look like and how they can be involved in the care and decision-making for their newborn.”

“Families should be part of the process of making health care decisions for their child,” Brelsford said. “We need to attend to the whole person in the family unit, offering them psychological and spiritual support.”

This research was funded by an internal Research Council Grant from Penn State Harrisburg. The authors disclose no conflict of interest. Lisa Nestler, Penn State Harrisburg, also contributed to this research.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.