We are Penn State Health: It’s all about the patients at St. Joseph’s lab

Darryl Weyandt is a guardian angel.

He has never met some of the people he’s watched grow up. For some of them, Weyandt works long hours helping doctors save their lives, even though he’s never been in the same room with them.

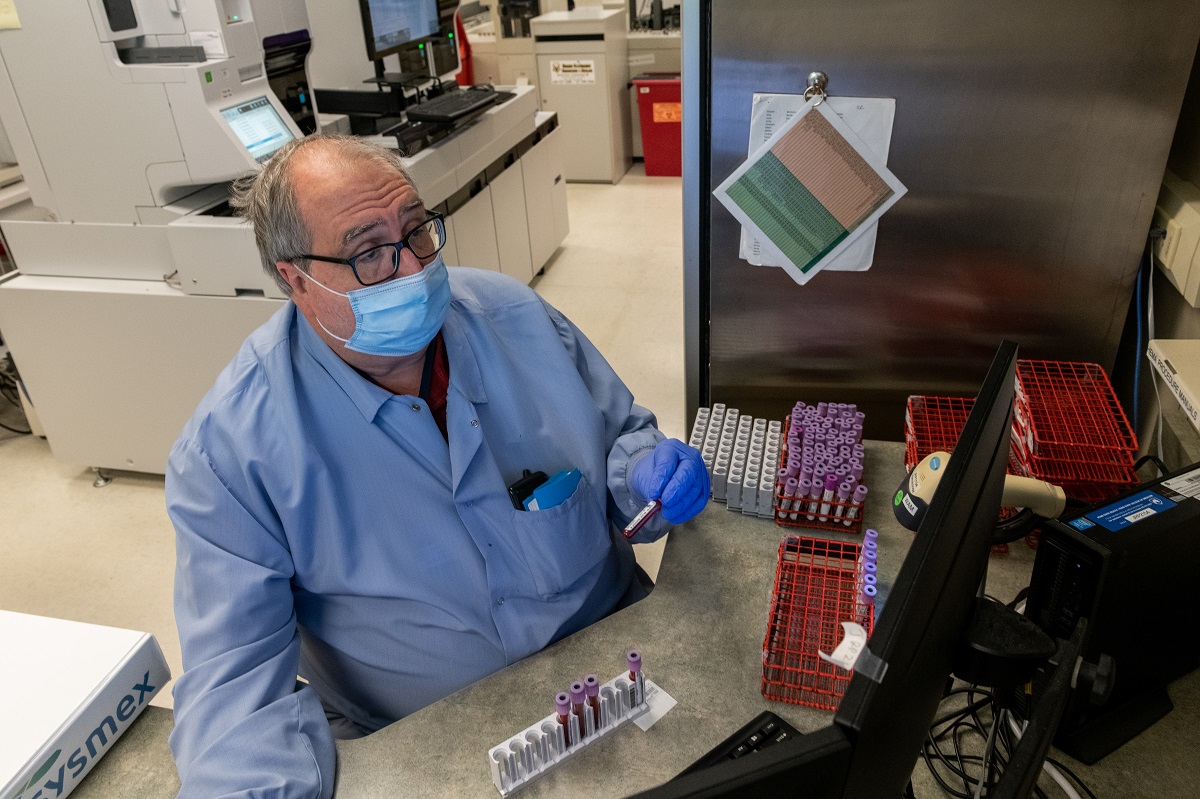

During more than 40 years as a lab technician at Penn State Health St. Joseph Medical Center, Weyandt has built relationships with patients from birth to middle age through tiny vials of the fluids their bodies use to function. He might not stand at their bedsides wielding a stethoscope and wearing a white coat, but Weyandt holds a stake in his patients’ recoveries. He feels the same highs and lows. And often, Weyandt and his colleagues have made all the difference.

Many of the 112 laboratory employees at St. Joseph came to their jobs after studying to become nurses or work bedside jobs, but their careers carried them behind the scenes. Others joined the lab team out of a love for science. Some are recovering chemistry teachers, or they knew they wanted a job in the medical profession, and this gig with microscopes, computers and vials is what spoke to them.

Many never leave, work the same jobs and watch the technology change like the seasons. Weyandt and his colleague in hematology Donna Re started during the Carter administration. Core Lab Manager John Thomas has been there since Reagan.

Ask any of them why they’re there.

To help patients, they’ll tell you.

Resilient people

Brandon Borrell slices tissue thin so pathology can examine the layer under a microscope.

On Sunday, March 8, Lab Director Linda Gallagher came into the hospital on Bernville Road in Reading for an emergency leadership meeting about the then-nascent pandemic. Almost overnight, the lab, which receives its specimens from the hospital and 12 satellite locations throughout Berks County, completely changed. Lab employees helped to staff a drive-thru testing operation and soon found their work dominated by tests for a pathogen none of them had seen before.

Months later, the coronavirus still dominates the work at the St. Joseph lab, but it has been assimilated into a workflow that involves thousands of blood, urine and tissue samples the team tests to help doctors and patients reach diagnoses.

“Any laboratorian will credit themselves that we are just resilient people, and we respond to any type of situation that is put to us,” Gallagher said. “I have a great team here. They’re awesome.”

Samples from throughout the hospital – sometimes more than a thousand a day ̶ arrive to the first-floor lab via pneumatic tube. Lab technicians like Darla Levy, who came to work there in July from a grocery store job, carry the barcoded vials from station to station, placing some of the tubes into centrifuges to separate the plasma.

“There are days that machine never stops,” Levy said, pointing to the large metal mouth where the vials arrive.

Colors denote priorities – yellow labels on vials come from emergency, green from medical oncology and blue from critical care.

Rapport

Hematology samples go to a corner of the lab ruled by a few bulky machines. Here, Weyandt, Re and colleagues such as Celeste Dimarco and Jinal Patel feed the vials into machines which scan for abnormalities. If nothing is wrong, conveyer belts ferry the blood to a freezer for storage.

When a machine finds something indicating illness, it creates a slide for further analysis by human eyes. Often, the lab team knows the diagnosis immediately. Other times, they consult with physicians.

“You develop a rapport with them that’s important,” Weyandt said.

The technologists have formed friendships. COVID cancelled their plans for a picnic on Re’s deck. They attend training sessions and teach classes together. Dimarco has worked there for 25 years.

“Between the three of us,” she said, meaning Weyandt and Re, “we have 100 years of experience.”

In the time they have left on the job, they’re working to impart some of that century’s worth of knowledge to Patel, who has been there seven years. Like many of her colleagues, Patel came to the job after first exploring a career in nursing.

“I knew I couldn’t be a nurse,” Re said.

“So did I,” Patel said, “but this allows me to work in health care.”

They stay for the science and the excitement of being on the forefront of new innovation. Most lab technicians say they just couldn’t see themselves working directly with patients.

But part of what someone like Weyandt has to teach Patel is more personal than scientific. Recently, Patel asked about a patient whom the hospital had been treating for decades. Weyandt immediately knew who the patient was. Knew all about him, even though he’d never seen him.

“He knew the name,” Patel marveled.

Machines

Conveyor belts ferry vials from machines to a storage facility.

In four decades, the job has become much faster. Many tasks were automated even back in the ‘70s when Weyandt and Re were newcomers. Now vials can be screened in the blink of an eye.

Thomas, who has worked in the lab for 32 years, remembers when the lab tested samples for electrolytes using an open flame. Now, as core lab manager — the captain of the ship, as co-worker Osiris Martinez Urquilla calls him – Thomas presides over a room of roaring computers capable of scanning cells faster and more accurately than any human being.

Thomas and Urquilla work in the Chemistry section of the lab, which sees the most traffic. If you get a blood screening for, say, cholesterol, this is where it comes.

Now, COVID test has added a significant volume of testing to Thomas’ business. “We pretty much establish the flowchart of what goes where,” he said. Some samples are tested in-house, others are sent to a testing company and still others are sent to Hershey Medical Center.

Histology, cytology

Histology and cytology offers a respite from the omnipresent roar of machines in the main part of the lab. Situated around a corner and near the back, Pathology Manager Tanya Abbott and colleagues like Pathologists’ Assistant Brandon Borrell work with fewer machines than their blood-focused co-workers.

Histology is the study of tissues and cytology focuses on fluids. Most of the specimens in this portion of the lab aren’t blood or urine in vials. In some cases, the tissue samples are large. One refrigerator holds legs, exclusively. “We have to put them somewhere,” Abbott explained. Legs are too large to fit in other specimen holding areas, so they get their own place.

“We also get foreign bodies,” Borrell said. He once received a turkey caller that got stuck in someone’s throat. “You do something different every day, and you never know what you’re going to get.”

The work mostly dried up at the height of COVID, when the hospital cut back on surgeries, and the satellite locations, from which histology and cytology receives about 30% of its business, cut back on surgeries and patients.

The six full-time employees from this portion of the lab volunteered for other duties. The hospital needed help in the COVID-19 unit. Borrell and a colleague worked as transcription lab assistants.

By summer, volume had increased. “In a hurry,” Abbott said, and she and her colleagues went back to their former jobs.

But their shift underscores the reason nearly every lab employee gives when asked why they do what they do.

“It’s about patient care,” Abbott said.

Even when sometimes the only part of the patients you see is their legs.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.