Can Jesse have this dance? Climbing back from cancer, Jesse King returns to THON

Little fanfare accompanied the return of THON’s King, but it was a phenomenon to those who knew.

Just after 5 p.m., Jesse King, last year’s volleyball chair of the event, called by some of his closest friends “the embodiment of THON™,” reached the latest height of his comeback tour: he walked into the Bryce Jordan Center at State College on his own two legs.

A few weeks after his last THON appearance in 2021, it seemed likely that would never happen again. Eleven months ago, King died on an operating table. Doctors managed to restart his heart, and that began a climb up what has become the tallest mountain of King’s life. And now, here he was, elbowing his way into a spot on the floor among 16,000 fellow Penn Staters for one of his great passions — the annual event where his classmates spend 46 hours on their feet to help defeat childhood cancer. This was the 50th anniversary.

King traded fist bumps with his Penn State Club Volleyball teammates. His big brown eyes never stopped moving and absorbing every moment.

Then, the dancing started, and King’s parents saw frustration. No one in the Bryce Jordan Center wanted to dance more than King, but for now, he can’t. Days after THON 2021, doctors performing a routine procedure discovered the 21-year-old had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He was in a coma, spent weeks in intensive care and had to learn to walk again. They tell him it’s a miracle he survived.

Every year, students compose a song for the hourly line dance. Among the lyrics this year: “Still we dance for those who can’t.”

Jesse King couldn’t quite manage the dance moves this year, but that’s OK. Now, his friends and family are dancing for him. Every day they watch him come back a little more. Sometimes the steps are so small only they notice. Sometimes he startles everyone by leaping to his feet and trying to dance.

It’s a race of inches for now. Those who love him are in it for the marathon.

Friends of Jesse King, center rear, sport t-shirts showing their support for him.

Bright future

Last March, Jesse developed a cough. He had trouble swallowing.

No big deal. A multisport athlete and captain of the Penn State club volleyball team, he seemed magically immune even to the scourge of his sophomore year, COVID-19. He’d been exposed more than once, and when others had had to fight off the illness, Jesse was always just fine. And, of course, there’d been THON. He’d been on his feet for 46 straight hours and barely batted an eye.

This cough wasn’t even going to register as a blip on his life’s radar screen. The 20-year-old sophomore was already planning next year. He’d room with volleyball mates Michael Wang, Alex Ryan, Adam Gallagher and Luke Pagan ― guys he’d known since he was a trash-talking volleyball player at Cumberland Valley High School. Ahead of him were two more years of college, and then, after he obtained his degree in hospitality, he’d make his dream a reality. He’d open his own sports memorabilia bar.

But before that there’d be two more THONs as a student. He’d been obsessed with the event even before Penn State … well, for Jesse there really was no BEFORE Penn State. His father, Jeff King, graduated in 1985; his mother, Wendy, in 1987. She danced at THON in 1986.

The first event Jesse chaired was the coronavirus version. Everyone had to dance on camera in their rooms to observe social distancing. They raised more than $10 million. “He was so excited about THON, even when we were freshmen,” said his co-chair Kelly Donis. “He was the one who pushed us to keep going.”

This cough, everyone knew, was just the King family hiccup. Jeff had had it, too ― a slight narrowing of the esophagus. Doctors perform a minor procedure, lower a tube down your throat, widen it a bit and you go on with your day.

So, the morning of his throat procedure, when his mom dropped him off at the hospital, he gave her a fist bump. “We’ll go to Chick-fil-A after,” he said. Then, he left her.

She wouldn’t hear his voice again for three months.

“I thought that was the last time I’d ever see him”

Lowering a device into his throat, his doctor discovered a massive tumor in his chest that wrapped around the tube through which Jesse breathed. There’s no telling how long it had been growing there, but it had deflated his right lung. Doctors believe he danced nearly two days and nights at the THON he chaired with a collapsed lung.

Then, as they removed the tube, Jesse’s respiratory system collapsed, and his heart stopped. Doctors revived him.

“They said he shouldn’t be here,” Jeff said. “He’s here for a reason.”

Wendy watched as paramedics loaded him onto a helicopter. “I thought that was the last time I’d ever see him,” she said.

They flew him from Mechanicsburg to Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, where doctors put him on life support. Wendy stayed as close to him as possible, counting tubes, checking in on every development. At first, they were all bad. He had damage in nearly every major organ, including, they discovered later, his brain.

Within days, doctors started him on round after round of chemotherapy to shrink the tumor.

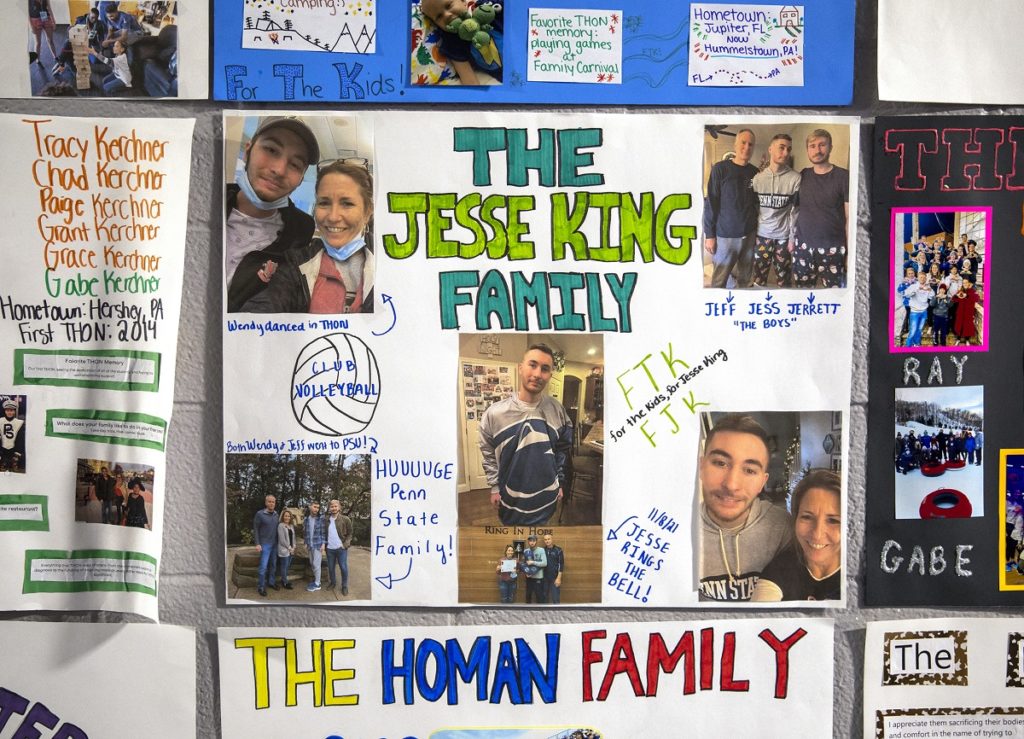

Jesse King’s supporters displayed this poster of Jesse King during THON.

‘Doing what we have to do’

Within the first 48 hours, as Wendy waited at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, someone from Four Diamonds® approached her. She knew all about Four Diamonds. She was a King, after all. But as she sat in a Hershey Medical Center hospital room hour after hour, searching for shreds of hope, medical bills hadn’t occurred to her, let alone that Four Diamonds might help with them. Four Diamonds is for little kids. Jesse was her baby, but did he qualify at 20?

Founded in 1972, the charity has helped thousands of families of children in just the Kings’ position, all the way up to age 22.

When Jesse emerged from his coma, the full breadth of what lay ahead of him began to come into focus. The Jesse who’d gone into the hospital in March had been gregarious, a comedian and cocky, according to his friends. The Jesse who opened his eyes weeks later stared out at the world from a face that had gone blank. He didn’t laugh or cry. He’d lost 40 pounds.

He began a wide array of therapies designed to bring back much of what he needed to relearn. He had to learn to walk again, and within days of coming out of the coma, therapists coaxed him onto his feet.

Finally, after 20 weeks at the hospital, Jesse went home. Gone were the weekly Penn State games that fall. Their son, who had before seemed impervious to illness, now had to be watched meticulously. “We were in a bubble,” Jeff said.

The community rallied around him. His high school volleyball and soccer teams sold T-shirts. His friends at Penn State started a GoFundMe page. It raised $48,000. Every donation means something, but when the Kings saw even small gifts of $5, they choked back tears. Those donations came from kids, they knew. Kids like Jesse.

His parents continue to pay his share of the rent for the apartment where he planned to live at Penn State. Sometimes they bring Jesse to visit. His roommates have reserved a space for him. He sprawls in the chairs like he’s making himself at home. Leaving is always hard. On the ride back to Mechanicsburg, they ask him if he misses his friends. He nods.

Some days he covers more ground than anyone expected. Jesse is walking again. He has a disorder called drop foot, which gives him a limp, but his gait seems to improve every day. He can do complex math problems. He recognizes all of his old friends.

Some days are frustrating. Jeff is admittedly the more emotional of the two. “I cried at their elementary school graduations,” he said, laughing. But Wendy has her moments. They lean on each other, and on his brother Jerett, a senior at the University of Alabama, who returns as often as he can.

People tell them they’re brave for staying so positive. Jeff shrugs. “We’re just doing what we have to do,” he said.

Determined

While Jesse couldn’t dance, THON sponsors dozens of events for families whose lives have been upended by cancer. That Saturday, the Kings took a tour of Beaver Stadium led by longtime Facilities Director Brad “Spider” Caldwell. Wendy and Jeff scarcely left Jesse’s side. Jeff stood next to him and kept an arm around his shoulder. They’re careful not to push too hard. “This is all new,” Jeff explained.

Jesse’s eyes never stopped moving. He gazed out onto the winter-yellow football field and stopped to peer at the writing on the old trophies or examine a jersey from the Fiesta Bowl in 1986.

A sign over the doorway between the locker room and the field contains a quote from author Henry Van Dyke, “Some succeed because they are destined to, but most succeed because they are determined to.”

“It’s a lot to take in, isn’t it?” his father asked.

Jesse looked at him. He is still there, inside the slender, shuffling frame. His cancer is in remission. Part of his life is a blank, and his short-term memory is spotty. Sometimes, he tries to speak or open his fingers to shake someone’s hand, but he just can’t make his body work. When they notice him trying, they ask, “Are you trying to say something, but you just can’t make the words?” He nods. Locked inside, the same old Jesse is in there, searching for the key.

Every day, he inches forward. Sometimes, the moves are barely a whisper. On other days, they’re a full-throated shout.

As the dancing started at the Bryce Jordan Center the first Friday night of THON 2022, Jesse had been seated. When everyone stood, he performed a miracle that surprised everyone.

He leapt to his feet and tried to dance.

That, he hadn’t done since his last THON.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.