The Medical Minute: Aortic dissection starts a race against the clock

Last October, Harold Weber won the most high-stakes race of his life.

Weber was working his job as a construction electrician when he began to feel ill. “It was a weird feeling I didn’t have before,” he said. “I had an awful taste in my mouth.”

He dialed 911, and when someone answered he blinked. When he opened his eyes, he was waking up in a hospital room at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. It was a month and a half later ― December, and someone was decorating his room for Christmas. He has no memory of what happened in between.

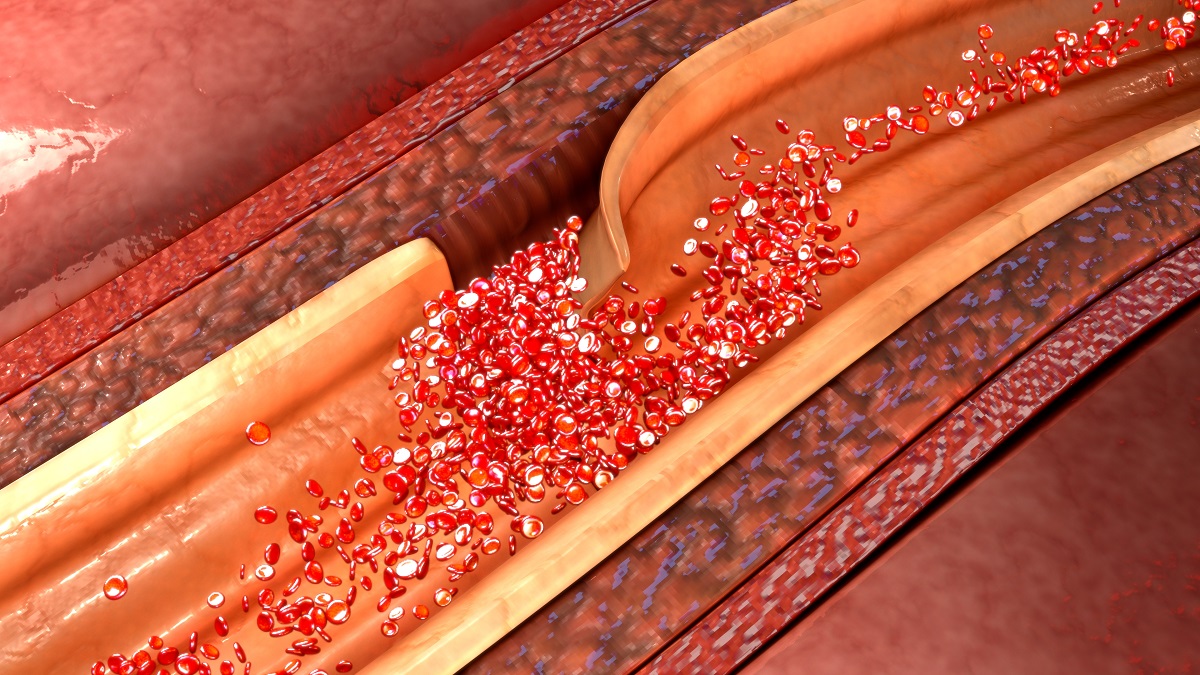

The lining on the inside of Weber’s aorta had split. The break created two channels, or lumen, on the interior of the blood vessel. The new channel, called a false lumen, could have ruptured at any moment. For most people, the condition, known as an aortic dissection, requires emergency open-heart surgery. And the longer it takes, the worse the chances. In fact, the odds of dying increase at a rate of about one percent every hour, said his doctor, Dr. Abdul Elnaggar, a cardiac surgeon at Penn State Heart and Vascular Institute.

It took a helicopter ride from Life Lion Emergency Medical Services and a leading-edge procedure called the Frozen Elephant Trunk to save the 63-year-old Ephrata resident’s life. Weber became the first patient in the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center’s history to undergo the procedure that Elnaggar says not only saves lives but improves the long-term outlook for people who suffer aortic dissections.

You guessed it: Caused by smoking, high blood pressure, cholesterol

Aortic dissections caused 9,904 deaths in the U.S. in 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High blood pressure and high cholesterol were among the culprits. A little more than half of the deaths were in men. In 75% of the deaths, a history of smoking was a factor.

The prognoses for aortic dissection patients are so dire that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends all men age 65 to 75 who have ever smoked should get an ultrasound screening for an abdominal aortic aneurysm, even if they have no symptoms.

And in some cases those symptoms can come on fast. They include sudden stabbing pain in the chest or jaw. Some patients lose consciousness.

Weber was lucky his dissection happened while he was awake. “People die in their sleep,” Elnaggar said. “Many don’t even make it to the hospital.”

The aorta is the biggest blood vessel in the body. From the top of your heart, it leads downward as the thoracic and abdominal aorta before splitting into the left and right iliac arteries in the legs. It’s a couple inches in diameter. Think of it as the body’s Mississippi River, the big channel away from the heart that distributes oxygen.

Better yet, think of it as an elephant’s trunk. That’s where the procedure that saved Weber and is continuing to save the lives of patients at Hershey Medical Center got its name.

The Frozen Elephant

Elnaggar learned the Frozen Elephant Trunk procedure while working as a fellow at Cleveland Clinic. Historically, when someone experiences a dissection, doctors repair the section of the artery where the split occurred. That saves the patient at first, Elnaggar said, but most patients who don’t receive the new procedure face more serious surgeries down the line.

Making the classic fix, the false lumen can continue to carry blood. That often it leads to a future aneurysm and rupture elsewhere further down the line. The new procedure halts the false lumen – freezes it – by the use of a large stent, big enough to push against the wall of the aorta and stop the false lumen.

The hope, Elnaggar says, is that the disruption is enough to prevent future aneurysms.

For Weber, one brush with death was plenty. He’s slowly learning to walk again after spending months in bed. His short-term memory still hasn’t completely recovered and he has yet to return to work.

But Elnaggar says his chances could be better because of the procedure he performed.

“For someone with 20 or 30 years left, that would greatly improve the quality of life,” he said.

Related content:

- The Medical Minute: Detection and treatment of aneurysms bring challenges

- The Medical Minute: Treatment options for heart failure

The Medical Minute is a weekly health news feature produced by Penn State Health. Articles feature the expertise of faculty, physicians and staff, and are designed to offer timely, relevant health information of interest to a broad audience.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.