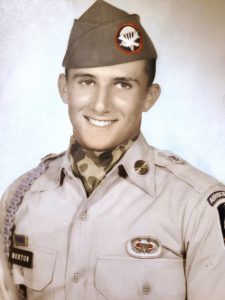

Jim’s phantoms: Wounded veteran finds freedom from pain 56 years later thanks to Hershey Medical Center procedure

As often as six times a week for more than half a century, Jim Morton awoke in the middle of the night with pain in his feet.

You’re shaking the bed, his wife would sometimes tell him.

Morton would lie back in the dark wait for the stabbing to go away. He couldn’t do anything else ─ couldn’t strip off his socks, rub where it hurt or stretch his toes.

The aching feet weren’t there.

They’d been blown from his body in a blast from an artillery shell in a jungle in Vietnam in 1966. The explosion killed one man, wounded another and took both Morton’s legs when he was 20 years old.

Six weeks ago, that half-century of torture became a memory. Dr. John Roberts, a plastic surgeon at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, performed a new procedure called targeted muscle reinnervation on Morton. For the first time since he learned to walk again on prosthetic limbs, the pain is mostly gone.

It began generations ago, a few weeks after Morton was wounded. At an Army hospital in Valley Forge, Pa., he told the doctors his feet were killing him. How could that be since he’d left both of them near the Dong Nai River in South Vietnam in an area they called War Zone D?

It’s in your head, the doctors told him.

Over the decades, the ghostly pain continued to haunt him. He spoke with other doctors. Like more than 85% of amputees, Morton had what they called phantom limb pain, and there wasn’t much they could do. They could give him pills, but Morton refused to take narcotics. They suggested Tylenol. Mostly, he just lived with the excruciating, almost nightly reminder of what had been and the day it all changed in a flash.

Roberts wasn’t sure targeted muscle reinnervation would work on a 76-year-old man with amputations in the so distant past.

But for the month and a half since the outpatient procedure, Morton hasn’t been tormented by pain he can’t reach in limbs he lost halfway across the globe 56 years ago.

“I’ve waited a long time for this miracle,” he said.

Two yellow balls of fire

Morton, who dropped out of high school in Western Pennsylvania in 1963 to join the Army, was attached to the 173rd Airborne Brigade of the 503rd Infantry Regiment.

One night 10 1/2 months into his tour in 1966, his unit camped in a spot in the jungle under a canopy of trees. Morton had a sinking feeling. “My first thought was, ‘This ain’t too good,'” he said. Ordinarily, there’d be more visibility so you might see your enemy.

At 3:20 a.m., an explosion woke him. He remembers two bursts ─ two yellow balls of fire that threw him backward.

Later, in a hospital in Saigon, a nurse told him both legs were gone. He’d lost his left three inches below the knee and his right six inches above. He learned a sergeant who had been sleeping nearby when the artillery had gone off had been killed. “I was just happy I wasn’t in a body bag,” Morton said.

Life on two legs

At the hospital in Valley Forge where the stabbing pains in his missing legs first started, doctors outfitted Morton with a pair of prosthetic ones.

At first, he moved home and tried a few jobs before eventually relocating to the Dillsburg area of York County. He got married and had two children. Now he’s a grandfather twice over with three great grandchildren. He liked to hunt and still focuses on trimming and landscaping his tree-spangled yard that looks across the rolling central Pennsylvania countryside. He’s retired. The prosthetic legs never slowed him down much.

But the pain in those limbs he’d lost continued on as the years gave way to decades. Sometimes they tingled. Sometimes the pain was poisonous and sharp. Often, the ache forecasted the weather – when the hurt was particularly bad, Morton knew a storm was rolling in.

‘Nerves need something to do’

Then, a friend who’d lost a limb in a car accident told Morton he should see Roberts. Roberts had gone to a hospital in Chicago to learn a new procedure that seemed to have positive effects on people like Morton with phantom limb pain.

The exact cause of phantom pain is still unknown, but it is thought to be the result of mixed messages that the brain continues to receive from the missing body part. It’s not uncommon that, uninterrupted, a nerve will continue to send messages back to the brain on an endless loop for the rest of someone’s life.

“Nerves need a place to go and something to do,” Roberts said.

Over the years, medical science has developed “upward of 150 procedures” for the treatment of phantom pain, Roberts said. Methods vary from cutting nerve endings off at the stump to capping them to burying the endings within the surrounding muscle.

Of the procedures, the latter – rerouting the amputated nerves back into the muscle – have been most successful. Seventy to 80% of patients showed some improvement with their phantom pain, Roberts said, but that still leaves a significant number of people with continued disability.

Targeted muscle reinnervation improves upon the concept. Instead of just implanting the nerve end blindly into a pack of muscle, the procedure removes the scar at the end of the nerve and

sutures the broken nerve to another that’s working properly at a place where it enters the muscle. For reasons not entirely clear to medical science, the redirected nerve picks up where its non-damaged counterpart is also working.

In short, the procedure gives the nerve something to do. Using sensors, researchers can see the activity in muscles where the broken nerve has been rerouted when a patient is asked to move a missing limb.

The development has far-reaching possibilities. By tracking these signals and pinpointing which muscle groups are activated, doctors can help patients with prosthetics have better control over the devices they use to replace missing limbs.

Still walking

People with phantom pains have also found the technique surprisingly effective, and they report sharp reductions in pain, Roberts said. But would it work on a man of 76 whose missing limbs had been aching since the Beatles were still making records?

“The brain does have a bit of plasticity to it,” Roberts said. “But I was very skeptical.”

Morton was ready to try anything to get rid of the pain, so Roberts performed the procedure. Morton went home the same day.

Weeks passed. The operation temporarily confined him to a wheelchair because he couldn’t walk on his prosthetics while his incisions healed.

The phantom pain hadn’t entirely abated. During that first six weeks, a storm rolled through town. Morton felt something. A hint of pain. But the stabbing ache that shook his legs, the sharp pain he endured decade after decade since he was a young man, through kids and grandkids and great-grandkids …

That was gone.

“I was shocked,” Roberts said.

A few weeks after the procedure, Morton again slipped on his metal legs. He continued to sit in his wheelchair but put on the prosthetics just to get used to wearing them. Before long he’ll walk on them again.

And now, finally, he’s adjusting to life without the other legs, the ones he left behind that until recently cried out to him with the all-too-frequent reminder that Morton walked away from that day in 1966.

He’s walking still.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.