Compassion in the war zone: Two chaplains in Hershey help caregivers

Sixteen years ago, the son of a dying woman opened Penn State Health Chaplain Kelly Fuddy’s eyes.

She was working as a resident chaplain in a hospital intensive care unit holding vigil for the woman, when the son – a military veteran in his 50s – asked the attending nurse, “How long do they let you do this job before they pull you out?”

The nurse looked at him. Midnight shifts like this one were typically quiet. Earlier, however, monitors shrieked, ambulances flew in, health care workers rushed through halls, and families wrestled with hope and tragedy.

“This is like a war zone,” the man explained. In the military, the tours of duty are generally six months or a year before a service member goes home.

The nurse laughed. “I’ve been doing this 21 years straight,” she said.

“It was a light bulb moment,” said Fuddy, who today is the staff-assigned chaplain at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Fuddy has continued to work as a chaplain, but for much of the past year her job has been new. Instead of patients, she offers comfort to caregivers. The Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and Penn State Health Children’s Hospital are among a small number of medical centers in the U.S. that assign chaplains specifically to health care workers.

Both Fuddy and her counterpart in the Children’s Hospital, Laura Ramsey, say jobs like nurse, doctor, therapist, environmental services technician and caregiver offer big rewards for hefty tolls.

Health care workers are buffeted by stressors at hospitals around the world. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among them are the ongoing risk for hazardous exposures to pathogens like COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, hazardous drugs, long work hours, and rotating and irregular shifts.

The danger is something called compassion fatigue ― an emotional paralysis that stanches a caregiver’s ability to care.

“It’s different for everyone,” said Ramsey, who experienced the early signs of it herself at her previous job as a patient-focused chaplain. After the day-in, day-out involvement in crises, tragedy and loss, some people have symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with physical manifestations, like racing pulse rates or feeling as though they might pass out when they walk into life-or-death situations. Others feel emotionally disconnected, Ramsey says. Some “start playing mind games with themselves” and find ways to cut corners or avoid difficult situations during work.

They combat it, both chaplains say, with self-care. And that’s where the chaplains come in. For centuries, the job of a chaplain has straddled both mental and spiritual realms ― where compassion fatigue lurks.

Delivering compassion

The job is three-fold:

- Managing crises – Fuddy and Ramsey regularly work with health care workers who are dealing with the after-effects of crises. They hold debriefings, where those affected talk about what they’ve gone through and attempt to get past it.

- Residual stress – The chaplains often support employees dealing with the accumulation of all the stressors of the job, and they help health care workers develop strategies for dealing with the day-in, day-out pressure.

- Proactive work – Fuddy and Ramsey meet with both recently graduated nurses and longtime professionals to help them head off the potential for problems like burnout and compassion fatigue. They offer courses in resiliency.

For some of the health care veterans, their work has been revolutionary. “Having been a nurse for almost 25 years this was not something that was discussed when I was in nursing school,” said S. Natasha Smithies-Race, nurse resource coordinator. “Nobody talked about the emotional and mental toll that seeing death and sickness would take on you. I almost lost my career because of this, so I am happy to see health care finally starting to talk about this ‘ugly’ subject.”

Validation from someone not at the bedside

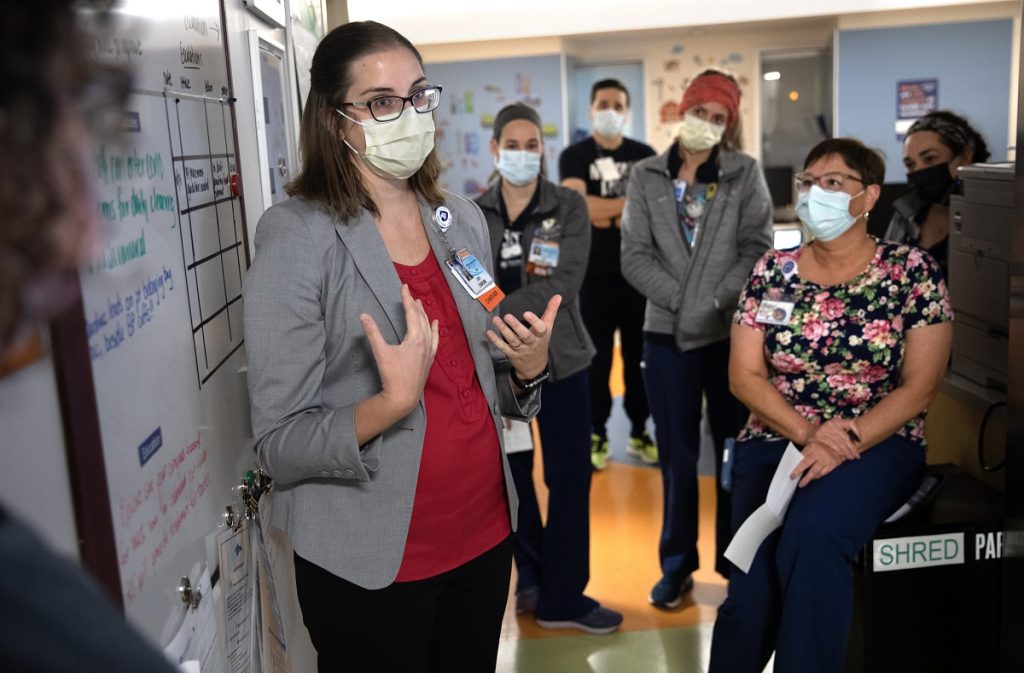

Like clinicians and other chaplains at Hershey Medical Center, Fuddy and Ramsey make rounds and huddle with their colleagues. Ramsey attends a 9 a.m. session at the Pediatric Progressive Care Unit, where the nursing team discusses what’s coming up for the day and what happened on previous shifts. One day in late October, for example, at a meeting where the staff dressed in Halloween costumes, Ramsey learned of a nurse who was assaulted by a patient overnight. She planned to follow up.

Dramatic as it sounds, Fuddy says those kinds of things happen frequently – patients in pain lashing out at caregivers.

After her meeting, she circled the hallways and introduced herself to staff she hadn’t met and checked in with old friends. “If you ever feel like you want to grab a cup of coffee,” she said to a new nurse there on her first day, “I’d be happy to.” She shook hands with passersby and complimented health care workers on their Halloween costumes. The encounters were quick.

“Honestly, the rounding is the hardest thing,” she said, “because everyone is so busy.”

But deeper work flows from these passing pleasantries. A few months ago, Ramsey bumped into Renae Epler, a nurse manager in the Pediatric Progressive Care Unit. Epler needed help. Her department had just begun accepting intermediate patients ― those who are medically stable, but unstable enough to need specialized care ― for the first time, and the added responsibility was stressing out her staff. “We were prepared,” Epler said, “but we weren’t mentally there yet.”

She and Ramsey ducked into an office and talked for a half hour. They developed a plan to give her staff a chance to express themselves about what they were going through in huddles and

writing down their feelings.

Since then, Ramsey has continued to be a regular fixture in the unit. “It has absolutely helped,” Epler said. “It helps [my team] feel validated by someone not at the bedside … that all the things they’re feeling are OK.”

Burnout and compassion fatigue can strike anyone, regardless of mental strength and stamina.

A 2021 study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found 22% of health care workers reported mild depression, anxiety and PTSD. Sixty-nine percent of physicians reported depression in fall 2020, 13% of physicians had thoughts of suicide, and 53% reported symptoms of a mental health condition like depression.

“One of the most beautiful things is that even though there’s a lot of burnout, a lot of people are able to be so resilient,” Fuddy said. “I admire it so much.”

They rebound through rituals. Taking time away from the job. Disconnecting on the drive home. Many who can’t take care of themselves for their own sake do it for their families. “People who work in health care are naturally other-oriented,” she said. “To do a good job they need the same compassion for themselves.”

Before her epiphany with the veteran in the hospital intensive care department years ago, Fuddy came to her job as a chaplain out of a job at a law firm. A friend had shadowed a hospital chaplain and told Fuddy about it. “This is it,” she thought, and eventually enrolled at a seminary full time.

Ramsey developed a bond with health care workers at Hershey as a child. Suffering from acute asthma, she was in and out of the hospital. “I remember the kindness of the nurses,” she said. “It had a strong effect on me.”

The importance of ritual

Some of the work, as you might imagine, is ceremonial. But the ceremonies are seldom empty.

For example, Ramsey and Fuddy bless rooms on a regular basis. Sometimes, the rooms are just random choices – a way to cleanse any bad energy that might be lurking.

When it’s tied to an event, the blessing of the room is more somber and attendance increases. When a child has died, for example, the chaplain’s prayer draws dozens of health care workers going through their own special kinds of grief. While they might not be related to the child by blood, the staff’s job was to soothe, treat and cure, and the perception of failure can devastate to the point of private anguish.

For all its science, medicine can be a superstitious business. Some nurses remember certain rooms as being unlucky or wear tattoos as talismans. Rituals like the blessing of the rooms matter.

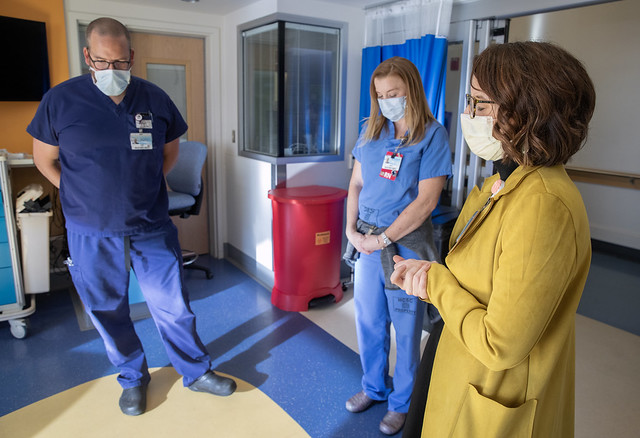

A few days after her rounds in the Pediatric Progressive Care Unit, Ramsey and Fuddy joined the last session of orientation when a new class of nurses gets ready to start new jobs at Hershey Medical Center.

Fuddy and Ramsey regularly perform a “blessing of the hands” with the incoming class – a ritual that for some connects them with the sacredness of their work.

At a podium in a conference room, Fuddy tells the gathered nurses about the time when she was 11 years old and had spinal meningitis. Her parents were out of town, and her grandparents had to bring her to Hershey Medical Center. A nurse had to take a blood sample. She was gentle. She gave Fuddy a stuffed animal. It was a small act of kindness, but “I will never forget her,” she said.

Then, Ramsey asked all the new nurses to hold their hands out and rest one palm on top of the other.

“Bless these hands in front of you that have touched life,” she said. “Bless these hands that have felt pain. Bless these hands that have been graced with compassion, drawn blood and given medicine. Bless these hands that have cleaned beds, anointed the sick and offered blessing. Bless these hands that have comforted the dying and held the future. And bless these hands that they may continue each day to be a blessing to others.”

Established in 1998, The Krapf Family Endowed Fund in Pastoral Services provides support for a variety of departmental activities, including ongoing educational and training opportunities for chaplains like Fuddy and Ramsey. Interested donors may join the Krapf family and others in enhancing spiritual care at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center by visiting engage.pennstatehealth.org/spiritualcare to make a gift. Contributions of $1,000 or more to the Chapel Fund at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, the Center for Religion and Health or the Krapf Family Endowed Fund in Pastoral Services are eligible for inclusion on the donor wall located in the lobby of the Krapf Interfaith Chapel.

Click the image below for a gallery of photos.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.