A GPS for your mind: Penn State Health’s Brainlab surgical system helps teen recover from hemorrhage

One day in April, Yassir Rosel toured the gray, folded landscape of his own brain.

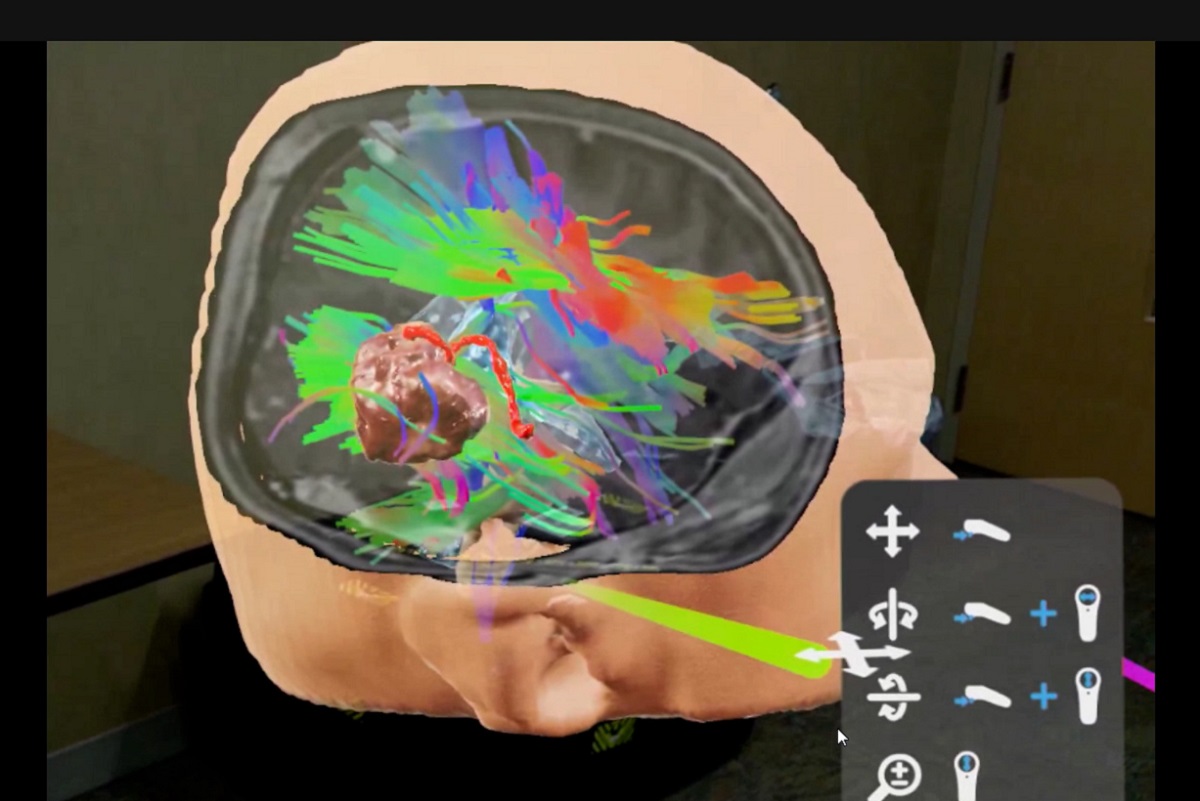

He liked video games, but he’d never played in virtual reality like this before ― or with stakes so high. Standing in a room in Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and looking through a pair of goggles, the 16-year-old watched a computer-generated hologram of a flesh-colored head. When his guide, neurosurgeon Dr. Ephraim Church, pointed at it, the head opened as easily as if it was made of water.

Inside was a 3D view of a world most people never get the chance to see ― the inner workings of his own mind.

And included in the image was a problem that months earlier nearly took Rosel’s life. After he suffered a seizure, doctors diagnosed an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), an abnormal cluster of blood vessels in his brain that had caused a hemorrhage, as the culprit.

Through the goggles, Church pointed to Rosel’s abnormality with what looked like a blue laser beam.

“See this red curly thing right here?” he asked Rosel, who was standing next to him in the room. “That’s the main feeder. So, the way these AVMs work is there are blood vessels coming into them, and they feed them.”

Church and Rosel were using a system called Brainlab, which couples computer-generated images with actual patient radiograph studies to create a mixed-reality perspective Church calls “a GPS for your brain.”

That day in April, they were planning for one of four operations Church mapped out to fix the cause of Rosel’s hemorrhage. For Church, the Brainlab system offers clarity ― a deepened understanding in exquisite, 3D detail of the exact location of a malformation in someone’s brain tissue and all the sensitive areas surrounding it.

For Rosel, it was a chance to meet his hidden, terrifying, would-be assailant face-to-face – and to see how Church would make it go away forever.

“We actually walked together through the hologram of his brain,” Church said. “I could say, ‘Here’s what I’m going to do.’ And, ‘Here’s how I’m going to keep you safe.’”

A frightening day in January

The hemorrhage had struck without warning. Rosel was a healthy teenager living in Wernersville, Berks County. An avid video gamer and a fan of the first-person shooter “Call of Duty: Black Ops,” he spent what time he could in fresh air playing basketball with friends. Illness didn’t enter the picture.

Then, on the evening of Jan. 12, while he was helping out in his parents’ restaurant, Paraiso Rosel Restaurante Mexicano in Robesonia, his head started to hurt. Pain radiated from the center of his skull. He told his mother, Yolanda Ramirez-Jiminez, who told him to sit down and see if it went away.

Rosel remembers getting up to go to the bathroom. “I guess I blacked out,” he said months later.

Ramirez-Jiminez said she heard Rosel collapse. She and her husband forced the door open and found him sprawled on the floor in the midst of a seizure.

An ambulance rushed Rosel to nearby Penn State Health St. Joseph Medical Center. By then, Rosel had regained consciousness. He seemed fine.

“Then they came in and said they were taking him to (the Milton S.) Hershey Medical Center,” Ramirez-Jiminez said. “It was hard to understand. How could he have blood in his brain? It was scary.”

Born with it

A blood vessel had burst, and Rosel’s brain was beginning to swell. His life was in danger.

To relieve the pressure, Dr. Church and his team at Hershey Medical Center removed a portion of his skull. They closed the skin incision without replacing the bone, allowing the brain to swell and then heal. For most of the year that followed, Rosel wore a protective helmet while his brain healed.

After he’d had a chance to recover from his emergency surgery, doctors diagnosed the AVM. Just over one in every 100,000 people have malformations similar to Rosel’s, according to National Institutes of Health statistics, though the agency acknowledges the condition is likely more prevalent but often undetected. The risk of hemorrhage from an AVM is 2% to 4% per year, and patients may also have seizures.

“He was born with it,” Church said. “It never caused a problem. Then, on Jan. 12, it started to bleed.”

A walk inside his brain

Removing the AVM required several operations in which Church used a catheter to enter Rosel’s brain through an artery in his leg and apply surgical glue to stop the blood from flowing to the blood vessels in the abnormality. The AVM was relatively large ― about 4 centimeters wide, Church said ― so it took multiple operations to slow down the blood flow safely.

Church and the neurosurgery team turned to their newly available Brainlab system to help plan their work.

Preparing for surgery, Church was able to virtually “walk inside the brain” and carefully study the inch-and-a-half area he planned to remove.

Using a combination of patient imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies and angiograms, the system created a hologram viewable from nearly every conceivable angle. The hologram also included detailed views of key fiber tracts responsible for movement, sensation and vision, providing a deep understanding of their relationship with the AVM.

“I could visualize in 3D the relationship between the AVM and those key structures,” Church said.

In August, Church performed the final operation ― 17 hours in duration ― to fully remove the AVM.

Later that month, Rosel returned to Hershey Medical Center. Church and craniofacial plastic surgeon Dr. Thomas Samson worked together to design a custom replacement for the portion of skull that was removed during the initial, emergency surgery. A 3D printer was used to craft the synthetic skull replacement and help Rosel look as if he never had these major brain operations. This surgery was performed in late August.

Back to everything I used to do

Rosel, now 17, returned to school in the fall. At last check, Ramirez-Jiminez said, he was getting As in every class.

He still hasn’t returned to the basketball court. Doctors want to be sure the replacement skull is fully healed.

But for now, video games are enough fun. The very real dangers he saw through those virtual reality goggles are gone. Now he can use computer-generated images the way he likes to ― for fun.

“I’m getting back to everything I used to do,” he said.

“When an AVM is fully removed, we consider it a cure,” said Church. “I enjoy thinking about all the wonderful things our young patients can go on to do. We can achieve a lot of good with these amazing technological advances, if we can learn to use them wisely.”

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.