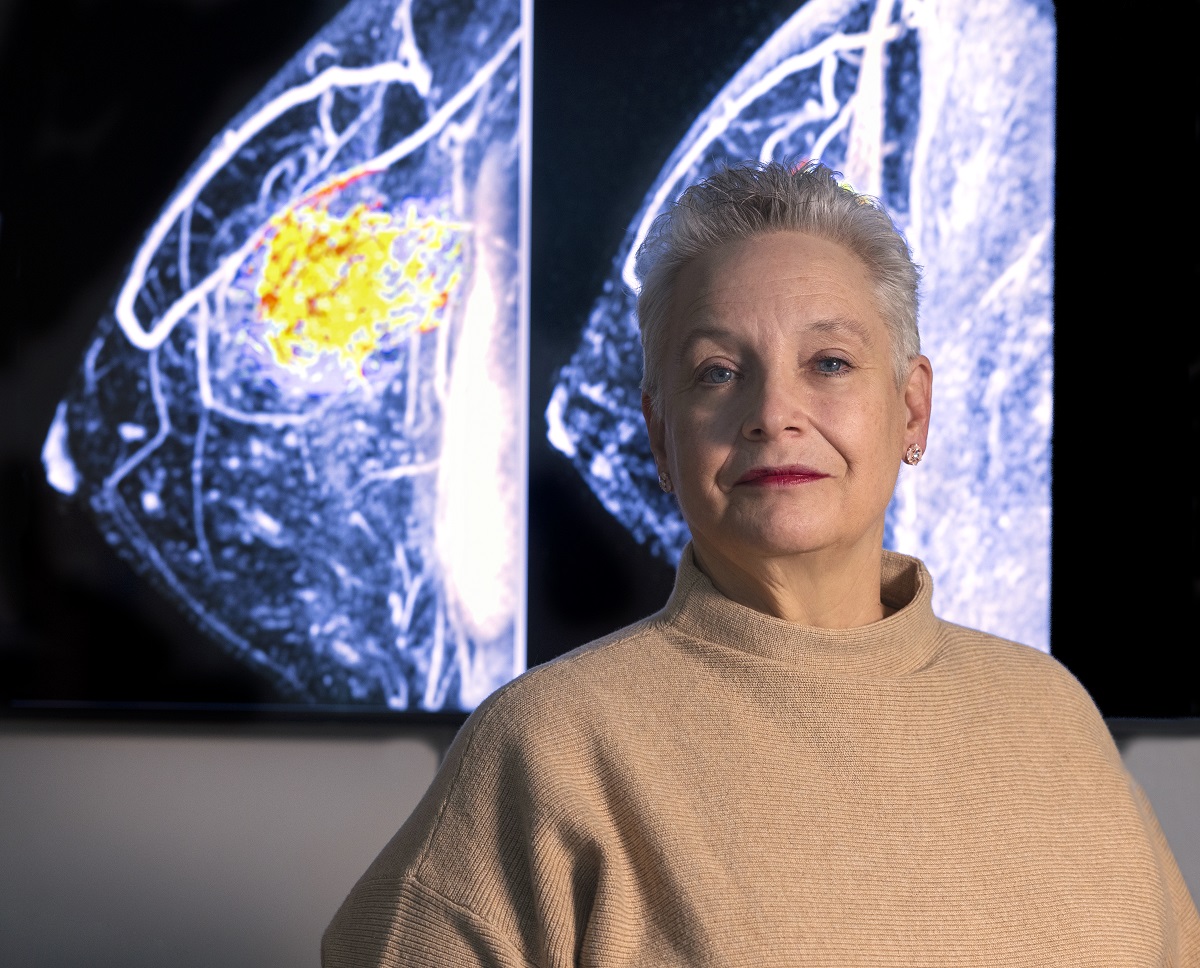

Doris Shank: Without clinical trials ‘people like me would have no hope’

My sister and I do a lot together, including getting our annual mammograms. It keeps us honest. On Dec. 7, 2022, we had our routine screenings. Hers was fine.

Mine was another story.

I was diagnosed with breast cancer. You could have knocked me over with a feather. The irony ― I am a cancer nurse and have been all my career. I am also the director of the Penn State Cancer Institute Clinical Trial Office.

My office manages all of the cancer clinical trials for all types of cancer. Clinical trials are so important in cancer care. They are what lead to Food and Drug Administration approvals, which make the drugs we use to treat cancer today possible. Without clinical trials, there would be no cancer treatment.

People like me would have no hope.

Chemotherapy is tough

The following month was a whirlwind. It appeared that we caught the cancer while it was contained to one breast. Then came biopsies, test after test to see if it had spread anywhere else, doctor visits galore, and finally, on Jan. 4, my first dose of chemotherapy.

Researchers have been refining the use of chemotherapy since the dawn of the 20th century. In 1919, a clinical trial was conducted on a patient with advanced lymphosarcoma using mustard gas. Just this year, Penn State Cancer Institute has participated in 10 treatment trials for breast cancer alone. All clinical trials at Penn State Health are conducted through Penn State College of Medicine.

Every week for 12 weeks I was given drugs to shrink my breast tumor and attempt to keep the cancer limited to one breast. Chemotherapy is tough. The side effects are tough. How it makes you feel about yourself as a woman is tough. Getting out of bed is tough. Did I mention that I worked during the entire treatment? Yep, that was tough too.

But here’s the thing ― I’m thankful for every one of these painful, uncomfortable moments. They save lives. They’re saving my life. And we owe all of it to clinical trials – to the people who volunteer to use their own bodies to further the science and to the researchers who tirelessly work to find new ways to stop what once seemed unstoppable. I’m also thankful for the team that I work with. Without them, I would have never made it.

Every drug I have received so far is the result of men and women participating in clinical trials that have shown these drugs are safe and effective in the treatment of breast cancer. The same applies to drugs for other cancers. The research toward a cure continues. The brave men and women that volunteer know that they are making a difference in the future treatment of breast cancer.

I lost my hair about five weeks after I started. Wigs ― what can I say. They serve a purpose but squeezing into one is like wearing a too-tight hat all the time. My eyebrows and lashes also disappeared.

Two weeks later, surgery. I received a bilateral mastectomy, and then came another surprise. The cancer had spread to two of my lymph nodes. I had known that the cancer in my breast had responded beautifully to the treatment, but I would need more chemotherapy.

Nuclear fallout

Now, on top of chemo, radiation.

The first use of radiation to treat cancer came in 1896. Since then, we’ve researched how to focus radiation more on the tumor, protecting the surrounding organs. We have also learned to give shorter courses of radiation to limit the side effects. Penn State Cancer Institute is currently running 18 trials that are investigating how to improve radiation therapy for cancer patients.

We decided to delay radiation because my incisions took a little longer to heal after surgery.

Learn more about clinical trials at Penn State College of Medicine and Penn State Health.

Radiation lasted for six weeks. Every day, Monday through Friday, I would go to the ground floor of the hospital for therapy. The radiation itself took all of five minutes. The challenge was getting my body in the same position on the treatment table to make sure that the same areas were getting radiated every day. That took a bit of time. Side effects were minimal. The biggest issue was being tired all the time.

All was well until the week after I finished. It felt as though my skin was on fire. One of the physicians in the department told me those feelings are very typical. They call it the “nuclear fallout.” It lasted four days. I survived.

I spent time with the lymphedema specialist. Lymph nodes drain fluid from my arm so it won’t blow up like a fish, but I had to have 31 of them removed. Preventative measures were in order. I perform exercises and wear special sleeves to prevent swelling in my right arm ― just more of the fun that goes along with having breast cancer.

Cancer free

Where am I now? My hair has grown back ― arrived about two months after surgery. The color went from whatever came out of the bottle to white and curly. It’s totally different from my pretreatment hair.

I am still receiving the chemotherapy and I’ll continue to until March or April of 2024. I am scheduled to have my second surgery in February. My original plan was to have breast expanders placed to stretch the skin and move to permanent implants with this surgery. I won’t do that now, because I managed to get an infection in the expander on my non-cancerous side and had it removed.

I’m going flat. I am okay with that.

As of my last set of scans, I am still cancer free.

I’m grateful to my doctors, nurses and health care workers and my team. They’re part of a long line of researchers and providers working arm-in-arm for more than a century that have brought me and countless patients like me to this moment.

Why tell my story? To make sure every woman out there gets her mammogram yearly. Being diagnosed with cancer is scary, but letting it go and having it spread when being caught early leads to a potential cure is the better option. If you feel a lump, get to your doctor.

One thing all the research agrees on: Waiting will not make it go away.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.