The voice: Four Diamonds-funded translator helps families struck by childhood cancer

As Aracilis Castillio watched her son gasping for air, she steeled herself for what was to come.

She hoped what was troubling her boy, 10-year-old Luis Yireh Cancel-Castillo, was something simple like fatigue. But when she and her husband, Luis Cancel, rushed him to a nearby hospital, they had resigned themselves to a different kind of struggle. The family moved from Puerto Rico to York five years ago. English is still challenging ― especially when it comes to talking with people in white coats, who seem to communicate in a third language of medical and scientific terms.

What came next for the family was far worse than anything they could have imagined. An X-ray revealed a dark spot in Luis’s chest. It turned out to be a large mass called T-lymphoblastic lymphoma. It had spread to his kidneys.

Luis was taken to Penn State Health Children’s Hospital, and then came two miracles. One has happened for nearly 5,000 families since 1972 ― a charity called Four Diamonds offered to pay any costs of his cancer care not covered by insurance.

The second was meeting Ernesto Garcia.

THON Weekend 2024 is Feb. 16 to 18. Donate today.

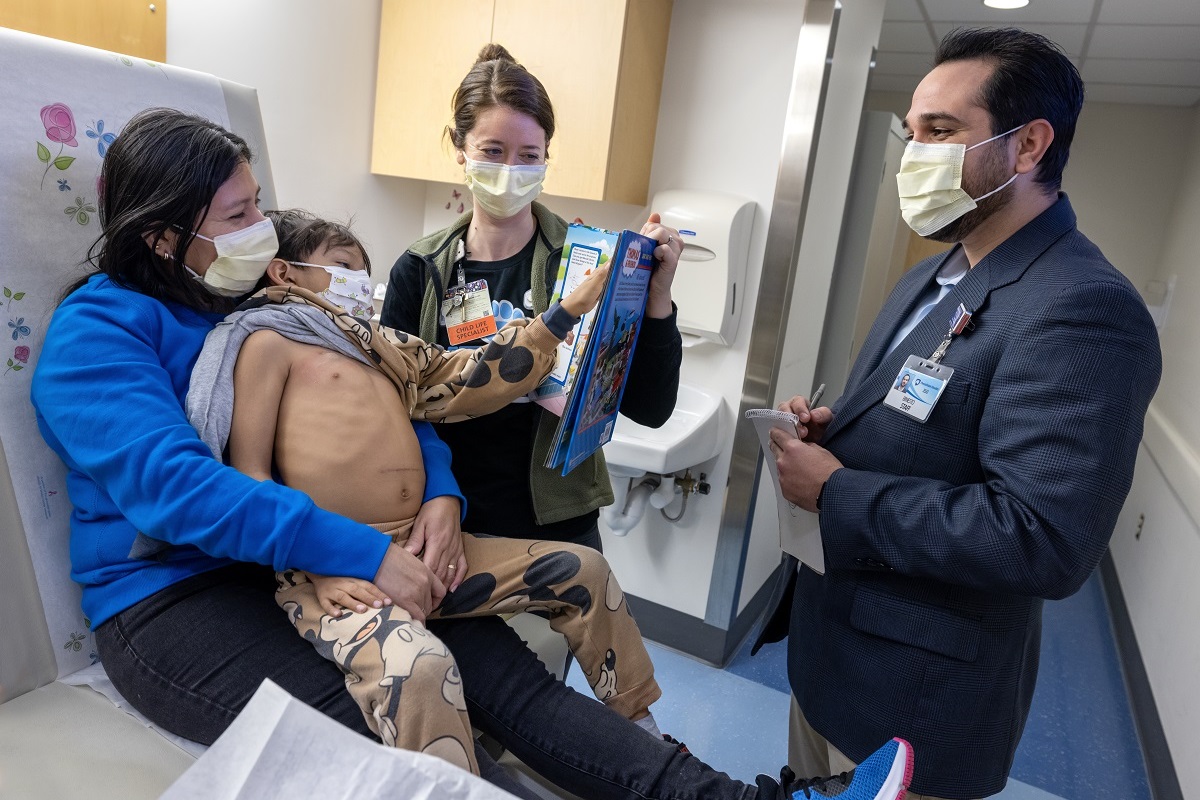

The family happened to arrive at Penn State Health Children’s Hospital on Garcia’s first day working as a medical interpreter in the pediatric hematology-oncology unit. Garcia’s position is funded by Four Diamonds, a nonprofit that pays for research and helps the families of children with cancer overcome the expenses incurred in their care. During the weekend of Feb. 16, thousands of people will pour into the Bryce Jordan Center at Penn State for THON, the annual charity event that culminates the year’s drive to raise millions for Four Diamonds.

And one outcome of it all: Families like the Cancel-Castillos who don’t speak English receive the gift of Garcia.

As the days and weeks of Luis’ recovery turned into months, Garcia has become more than a friendly face that turns Spanish to English and back again for Cancel-Castillos. Garcia has become an appendage. His job requires the soft-spoken man from Cuba to convey not just words but emotions.

To do it just right, Garcia has to, in a sense, become the families he’s translating for. As a result, he has lived many lives during his short time at Penn State Health Children’s Hospital. Often, they are lives in turmoil. When a family sees a breakthrough in their care, he celebrates. And when a child dies, it’s as though Garcia’s child has died.

“I’m their voice,” Garcia said.

From Cuba to the U.S.

More than 32% of the population speaks English “less than very well,” according to the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Language barriers, cultural differences and the often challenging nomenclature of modern medicine can make a give-and-take with a doctor a daunting task in the U.S. ― especially for someone who doesn’t speak English fluently.

It can be so daunting that many just give up and don’t get the care they need, said Misty Bowman, manager for patient- and family-centered care at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Bowman helps oversee and organize a growing number of Penn State Health interpreters.

They found Garcia. He’d grown up in Cuba in a medical family. Father, brother and mother all work in medicine.

In Cuba, Garcia used his language skills in a job as a diplomatic interpreter. Here, he volunteered for a year at a clinic and found medical interpreting was unlike anything he’d ever done before.

“It’s much more personal,” he said.

Conveying and controlling emotions

Garcia shares an office in a corner of a small room off the entrance to the pediatric hematology-oncology wing. Just across a span of tile floor behind a bank of computers is a wall mural showing THON dancers blanketing the stands and center court of the packed Bryce Jordan Center.

During his few moments of downtime, Garcia pores over medical terms he’s heard from a doctor. He Googles, studies and calls his medical expert family. He grew up with medical terminology, but he still has a lot to learn.

Garcia usually helps about four families each day. Many of the patients Garcia meets have shut down. Language is an immovable object. They smile politely, expecting to be confused. Then he introduces himself and speaks their language and watches their confidence swell.

Seeing families day in and day out, gaining their trust and interpreting their emotions, he forms bonds. “That connection is crucial,” Garcia said. But like all health care workers he struggles with boundaries. He resists the urge to help them outside of work and fights through his grief and elation to maintain as much detached professionalism.

“The most challenging thing is controlling my emotions,” he said, while conveying theirs.

When it’s working best, families and medical staff forget he’s there at all. People ask questions, and doctors provide answers and barely look at him. Nobody notices the language barrier has toppled.

‘We want Ernesto’

Luis’s bed is up a few floors from Garcia’s office. When he receives a call, Garcia strides in the room, smiling at the health care workers who have in four months gotten to know him. When an interpreter like Garcia is unavailable, Penn State Health and other health systems rely on a video interpreting service on a computer tablet where a remote interpreter translates a variety of languages. They prefer him.

“I think having someone there to interpret for families has a profound impact on the relationships we’re able to build,” said Dr. Gayle Smink, Luis’s oncologist.

For in-depth conversations, if you’re not speaking to a computer, you’re able to look a family in the eye, said Nicole Sites, a pediatric hematology-oncology nurse. That makes emotional connection, she said. “It’s not unlike us to go over and give a patient a hug,” she said. “And it’s easier to do that with Ernesto.”

Inside Luis’s room is dim. The boy lies on his side in the hospital bed. The brown eyes glance up from a computer tablet as Ernesto enters the room. Luis doesn’t need Ernesto’s services ― he speaks English, but the two are friends. Earlier, Luis had bested him at a video game. “I’m going to beat you,” Ernesto promises. “You know I will.”

His mother and father slump in their chairs by the window, but they smile. They’ve been mostly living in the hospital at Luis’s sides for two months. Luis has undergone chemotherapy and is responding well, the doctors say. But he developed a fungal infection that now doctors are attempting to stop before continuing his treatment. He’s bouncing back.

The boy’s parents are grateful for Four Diamonds, but they’ve never heard of THON. Maybe one day Luis will go there. For now, they just want him back safe and sound, playing the drums like he was learning to at home. Maybe one day he’ll play them on the stage of the Bryce Jordan Center during the annual talent show.

Through most of the steps of their dark journey, Garcia has been there to help light the way. During his first day on the job, he was receiving a tour and passing by Luis’s room. The nurses asked if he’d like to help. That’s how they met.

Luis’s parents don’t like the electronic solution to their voice, the computer tablet with the camera. “We hate the little camera,” Aracilis said. She knows a smattering of English, enough to realize the machine sometimes is saying the wrong thing.

“We want Ernesto,” she tells the doctors.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.