‘I wanted to change the outcomes’: Sholler’s career leads to neuroblastoma breakthrough

The little boy’s name was Tyler, and when he died, everything changed.

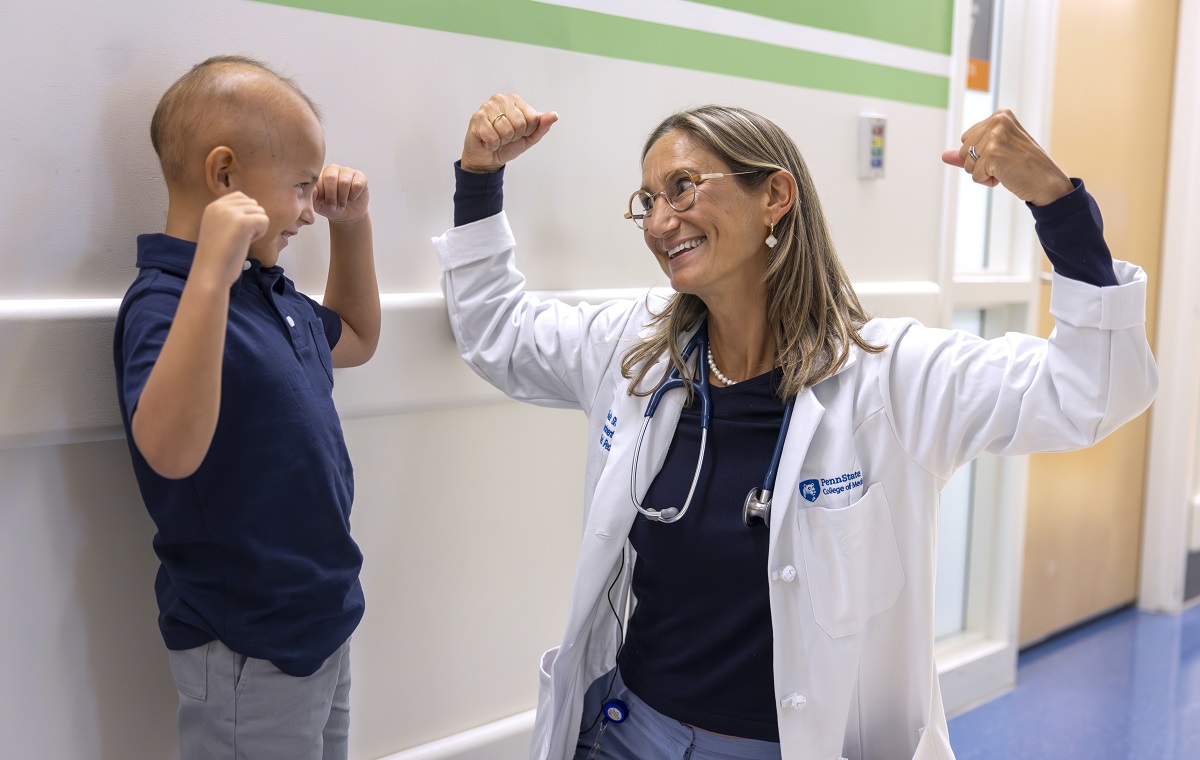

His oncologist, Dr. Giselle Saulnier Sholler, was a fellow at the time, fresh from her first three years doing clinical work in pediatrics. She was a new mom with two kids at home she was thrilled to see at the end of every day.

Tyler was the first patient she ever lost. He’d been diagnosed with neuroblastoma, an aggressive, cruelly resurgent cancer that infects mostly children younger than 6. Nine months later, Tyler had passed away.

It shook Sholler to her core. “It was really hard,” she said. She considered quitting. Then, two months later, Tyler’s mother wrote her a letter. Sholler was startled – this woman who had lost everything was actually thanking her.

“I had helped them through that journey,” she said.

After that, Sholler found a new path. She decided to stay in pediatric oncology, but her focus from that day forward became neuroblastoma.

“I wanted to change the outcomes,” she said.

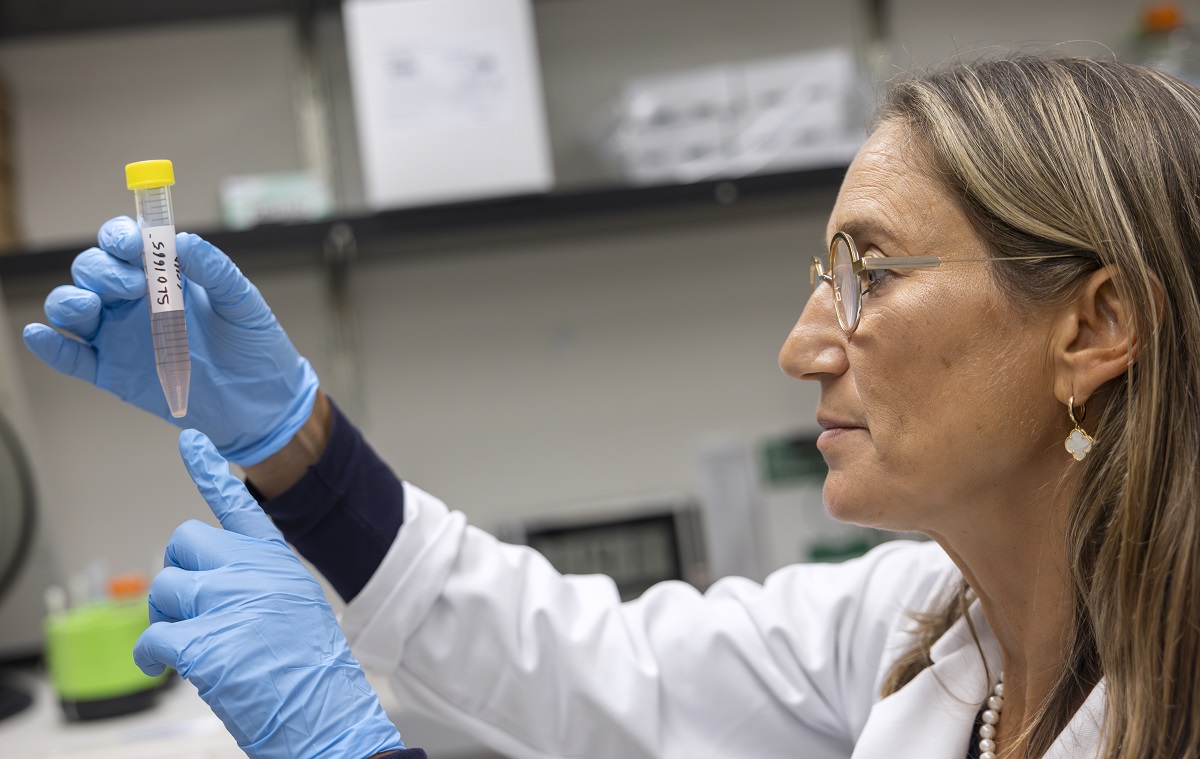

Two decades later, she’s doing just that. She and a group of backers – mostly families of children with childhood cancer – have cleared steep obstacles to research a drug called eflornithine (DFMO). The drug’s effectiveness in stopping neuroblastoma is already becoming legendary. In December 2023, the drug notched an important milestone: it received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). And as news of its effectiveness continues to spread, patients around the world are looking to Sholler and DFMO as the answer to a question many were afraid to ask – is their hope?

Maintenance therapy

Among the biggest problems many neuroblastoma patients face is relapse, Sholler said. Chemotherapy, radiation and other kinds of therapy can initially knock the cancer back to the point of remission. But often ― as frequently as 50% of the time ― the cancer comes back.

“We needed a maintenance therapy,” Sholler said. “With DFMO added at the end (of treatment) for two years, they take a pill twice a day, they go back to school and their immune systems are fine.”

In the trials with DFMO she’s been working on for nearly 15 years, the relapse rates among people who take the drug fell from 50% of the cases to 15%.

In September 2023, Sholler took over as chief of Penn State Health Children’s Hospital’s Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. She’d gotten to know some of the doctors from the Children’s Hospital through the Beat Childhood Cancer Research Consortium and came to visit.

“I was really surprised at the amount of research that goes on here,” she said. “There are nine oncology labs here ― pediatric oncology labs that are developing different medications and treatment options that would be perfect for our consortium to translate into clinical trials.”

The commitment to research at Penn State College of Medicine and the Penn State Cancer Institute as well as connections to programs like Four Diamonds, with its focus on funding research and assisting families directly, made it a perfect fit to continue the mission she began 22 years ago.

Families step in to help

When Tyler died, Sholler started working on drug discovery and research. During her second year as a fellow, she found an unapproved drug used to treat an African blood disease had, as a side effect, what looked like an ability to stop neuroblastoma.

When she decided to launch phase one of her own clinical trial of that drug in 2007, she received help from old friends and mentors to get started. Funding for childhood cancer studies is sometimes hard to come by, she said. Of all the money the federal government gives to cancer research, only about 4% goes to pediatric cancer. Sholler needed $100,000 to launch her trial.

So, another friend wrote her a check ― Tyler’s parents.

“That’s how the funding started for all of our clinical trials,” Sholler said. “They’re mostly funded by parents of children with cancer.”

That first trial had some positive outcomes, and that drug is still being discussed – but, more importantly, it turned out to be the first salvo in a career of research and trial and error that’s leading to proven results.

And at every turn, parents touched by childhood cancer have been there to help.

She assisted in forming the Beat Childhood Cancer Foundation, where parents help raise money for clinical trials. And through the Beat Childhood Cancer Research Consortium, Sholler has gone on to open 28 trials – two or three each year – with more than 55 hospitals participating.

Like the first trial, DFMO was also an antiparasitic drug that combatted African sleeping sickness. It’s been found to have suppressed a gene called MYCN that drives neuroblastoma.

Phase one of the trial was tested on pediatric neuroblastoma patients who had relapsed multiple times and were out of options. These children had active neuroblastoma, because the first test was geared to find out if DFMO could stop the existing disease – not prevent a relapse.

The findings led her to start testing the drug’s ability to prevent neuroblastoma tumors from even forming. The test subjects were mice injected with neuroblastoma. Mice that drank plain drinking water developed tumors. Mice that drank water with DFMO did not.

That changed the direction of the tests to focus on preventing neuroblastoma’s insidious ability to return. Pat Lacey, the father of one of the test subjects – a little boy named Will Lacey – and founder of the Beat Childhood Cancer Foundation, paid to fund the study. DFMO saved Will’s life. Today, he’s a college student.

From the heart

Then came a setback. The pharmaceutical company that was helping to supply the research stopped providing drugs.

Meryl Witmer, an accomplished New York investment banker and a director at Berkshire Hathaway, stepped in to help. Her son had battled a brain tumor. “She said she knew she could. And she knew the kids needed it. And she couldn’t live with herself if she didn’t,” Sholler said. Witmer ran the company for seven years, producing the drug so Sholler could complete phase 2 of the study.

Later, Kristen Gullo, a senior vice president at US WorldMeds, made the connection with her company that ultimately led to them backing DFMO’s bid for FDA approval.

It was yet another in a webwork of childhood cancer connections. Gullo’s nephew, Finn Johnson, had been diagnosed with neuroblastoma. When she found out, Gullo called her friend Lacey. Lacey connected her with Sholler, who treated Finn. Today, Finn is doing well.

The patent name for DFMO is now Iwilfin – Will for Will Lacey. Fin for Finn Johnson.

“In pediatrics,” Sholler said, “it all has to come from the heart. It’s amazing how much of this has been the right place at the right time.”

These days, the outpouring from families both grateful and hopeful for her help has been constant. Among the decorations in her office are photos of children who now have futures, thanks to her work. She receives letters, emails and cards from all over the world.

It began with one piece of mail. Twenty-two years ago, Tyler’s mom wrote to Sholler to say she was grateful someone cared.

“I’m so thankful,” she says.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.