Lack of antibodies, T cell deficiency drive degenerative brain disease development

Progressive multifocal leukoencepalopathy (PML) is a degenerative brain disease caused by a virus in some immunocompromised patients, especially those with T-cell deficiencies. Therapies that modulate immune system function are sometimes used to treat conditions like multiple sclerosis and cancer. However, this immune suppression in patients can sometimes lead to the emergence of harmful variants of the human polyomavirus (JCPyV), which can cause PML.

“We wanted to unravel some of the early steps that lead to the emergence of virulent strains of JCPyV,” said Aron Lukacher, MD, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Penn State College of Medicine. “Although it persists lifelong in most humans, JCPyV can lead to PML in patients with weakened immune systems. Understanding the specific conditions that cause PML to develop is important as the number of drugs associated with the condition increases.”

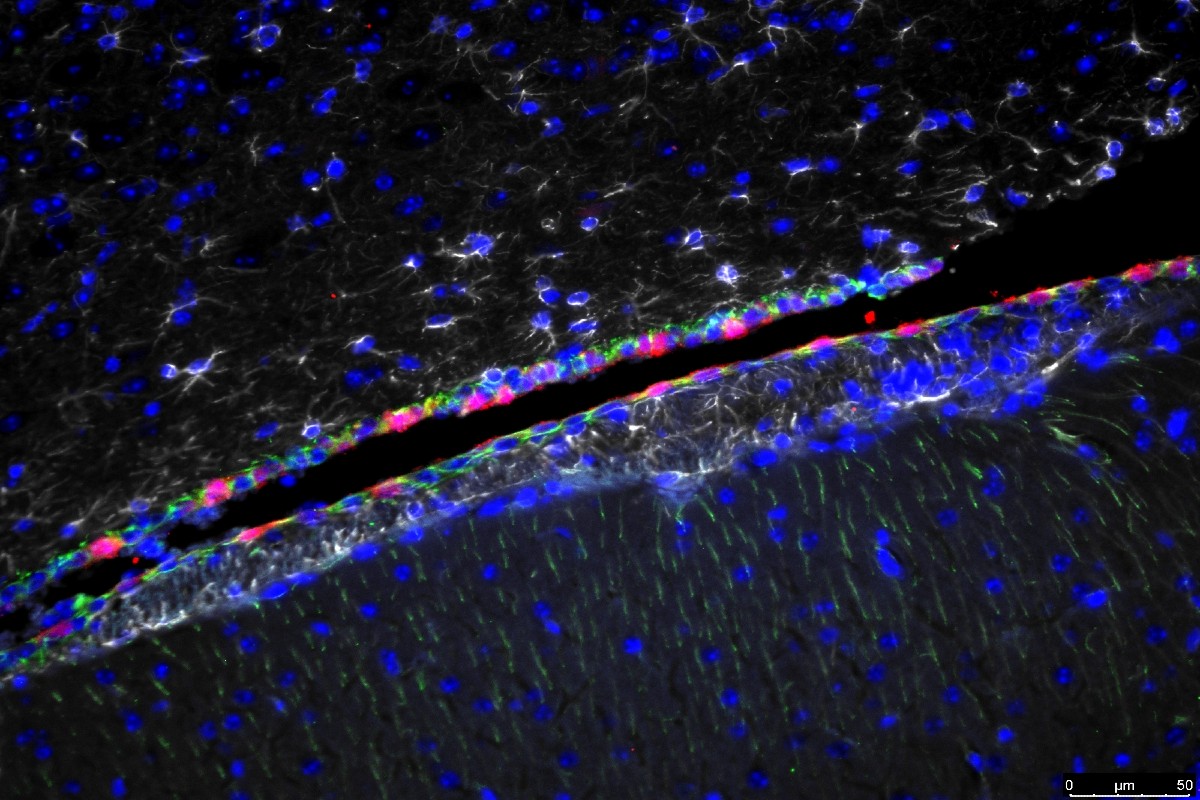

Lukacher and Matthew Lauver, PhD, postdoctoral scholar, and members of their lab recently published data that may explain why it can take a long time – sometimes years – for PML to develop after a patient starts an immune suppressing therapy. Using a mouse model of PML they developed, the team previously found that mutations in the virus’ capsid, or shell, allow it to escape detection from neutralizing antibodies. They used that same model to examine components of the immune system to see what factors cause the virus to mutate and escape immune control.

The Lukacher and Lauver found that a type of T lymphocyte called CD4 T cells are responsible for keeping capsid mutant variants of mouse polyomavirus (MuPyV) in check in the kidney, the major organ where MyPyV and JCPyV persist. Combined with a limited antibody response, which might happen in patients taking immune suppressing therapies, mutant viruses can develop and result in PML development. The research outlining these findings, was published in the journal e-Life on Nov. 7.

“PML is a rare disease,” Lauver said. “Our results offer an explanation for this rarity, while also pointing to some possible prevention strategies.”

Lukacher said moving forward, the lab plans to further study how CD4 T cells in the kidney keep polyomaviruses in check and also map sites on the capsid that are recognized by antiviral antibodies in healthy mice as well as those deficient in CD4 T cells. Their long-term goal is to develop a way to identify capsid mutant JCPyVs in the blood of patients on PML-associated drugs before the virus infects the brain and causes irreversible disease.

Matthew Lauver, Ge Jin, Katelyn Ayers, Sarah Carey, Charles Specht and Catherine Abendroth of Penn State College of Medicine also contributed to this research. The researchers declare no conflicts of interest.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. This research was also through use of Penn State College of Medicine’s Flow Cytometry Core Facility and Comparative Medicine Histology Core.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.