An artificial heart saved my life: LVAD patients and families share stories at reunion

By Bonnie Adams

Al Dolatoski felt short of breath and just didn’t feel well on Dec. 16, so his wife took him to an area hospital. There, he suffered a massive heart attack and underwent emergency heart bypass surgery.

Joyce Dolatoski remembers the panic she felt when he repeatedly coded in the intensive care unit and was resuscitated five times. She was relieved when told that he was being flown to Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center.

The couple told their story at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center’s annual Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVAD) Reunion on April 26. The six patients who attended share a history of severe heart failure that required an LVAD to pump blood throughout their bodies. About the size of a D battery, the devices can be used as a bridge to a heart transplant or as an alternative to transplant.

Dolatoski, 72, received his LVAD on Jan. 9 and describe it as life-changing. He uses a wheelchair but is learning to walk again and now feels well enough to work from home.

Dolatoski, 72, received his LVAD on Jan. 9 and describe it as life-changing. He uses a wheelchair but is learning to walk again and now feels well enough to work from home.

“I’m getting stronger,” he said. His wife said his kidney and cardiac function are so improved that he no longer needs dialysis and, in a rare turn of events, will eventually have the LVAD removed.

“They told him he was a miracle,” she said. “The LVAD team is great.”

The reunion was a celebration of life, with dinner, a cake and even karaoke music. “I Got You Babe,” the Dolatoskis sang to each other.

“It’s a pleasure to see how well everyone is doing,” said Dr. Howard Eisen, an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiology specialist, looking around the room. The group laughed when he described the old cardiac device’s noisy clicking sound that used to require him to speak very loudly at such gatherings.

Eisen has worked with ventricular assist devices since 1993. “It’s unbelievable how much the technology has improved since then,” he said. Hershey Medical Center uses the newest LVAD, the HeartMate III, which increases patients’ survivability and lowers the risk of stroke and gastrointestinal bleeding compared to older models.

Patients can expect to live 10 or more years with an LVAD, and the technology and treatment options are always improving.

“We offer many therapies for heart failure patients at Penn State Heart and Vascular Institute,” Eisen said, “including heart transplant, cardiac resynchronization therapy ― special pacemakers ― defibrillators and state-of-the-art medical therapies. We also offer less invasive valve replacements, trans catheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and mitraClip.”

The Heart and Vascular Institute has performed nine implants so far in 2019 and is currently providing care for 82 LVAD patients, said registered nurse Peggy Higby, the LVAD and heart transplant manager. Some Heart and Vascular Institute staff members were unable to attend the reunion that day because they were assisting with another LVAD procedure.

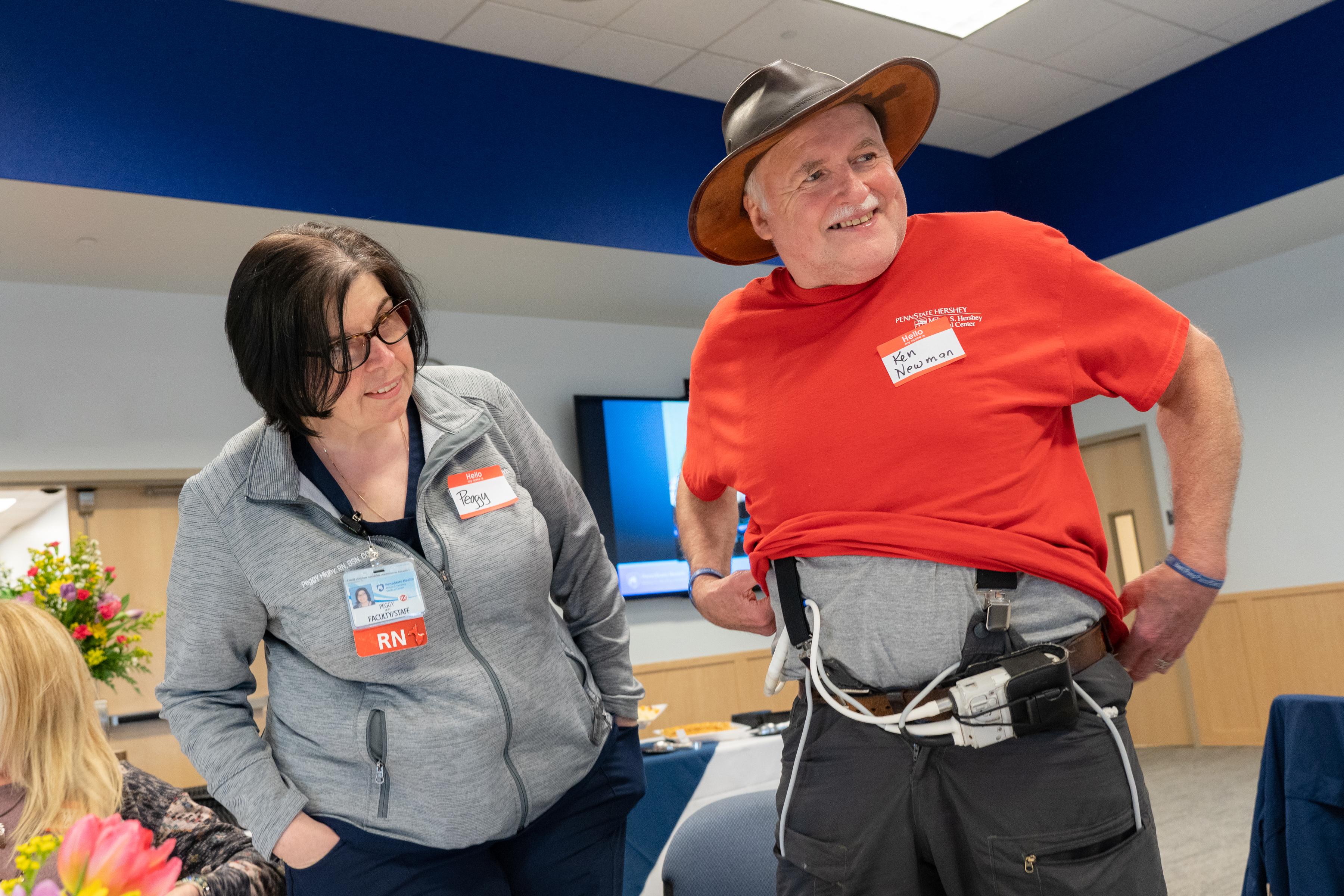

Ken Newman, right, shows off his HeartMate II LVAD to Peggy Higby, the LVAD and heart transplant manager.

For Ken Newman, the LVAD is buying him time as he awaits a heart transplant. He and his wife, Denise, said they attend the reunion each year, in part, as a way of thanking Hershey Medical Center staff.

“When you come here, it makes you feel you have hope,” said Newman. The 66-year-old from Herndon, Pa., received his LVAD two years ago and is now able to climb stairs and travel with his wife in their motor home.

Ken and Pam Zimmerman of from Conestoga, Pa., said they enjoy reconnecting with patients and staff at the reunion. After suffering a heart attack in 2008, Zimmerman recovered but had shortness of breath with activity, fluid retention and sensitivity to cold.

His health took a quick downturn in 2016 before his cardiologist Dr. Eric Popjes decided his best chance for survival was an LVAD. Pam Zimmerman said the symptoms her husband experienced before his LVAD are now gone

“We really appreciate Hershey, the doctors and the entire Heart and Vascular team,” she said.

Shirley Boyer, 65, of Newmanstown remembers how poorly she felt before her LVAD as she waited for a transplant. “I was fatigued all the time,” she said. Her heart’s ejection fraction, the percentage of blood leaving the heart with each contraction, was only 15 percent, compared to at least 55 percent in a healthy heart.

Her physical condition worsened to the point that a transplant was no longer an option. Dr. John Boehmer recommended an LVAD. Now two years after surgery, Boyer reports that she feels good. “She likes Hershey Medical Center and the nurses and doctors. She just feels at home up there,” her husband, Dennis, said.

As Joyce Dolatoski looks back on her husband’s journey to survival, she credits prayers, support from her family and Hershey Medical Center staff for helping both of them through their ordeal.

“They were caring not only for Al, but for me,” she said.

Transplant assistant Aimee Zehring reacts to Al Dolatoski’s thank you speech during the reunion.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.