Penn State Health doctors help Ephrata baby born with rare condition breathe easier

There was nothing unusual about Natasha Himes’s seventh pregnancy or delivery. Like her previous six, both were easy and uncomplicated. While all of her other children were born in a hospital, the Ephrata woman wanted to have this baby at home.

Dec. 19, 2018, started out as any ordinary day. Himes’ children, ranging in age from 2 to 13, completed their homeschool lessons, and the midwife visited. The baby wasn’t due until Christmas, but he had other plans.

At 3:53 p.m., Knoxley came into the world, weighing 8 pounds, 8 ounces, and 21 inches long. “I was in labor just 53 minutes,” Himes said. “The midwife walked in as I was pushing.”

When the midwife saw Knoxley had a cleft palate, he was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit at WellSpan Ephrata Community Hospital where he was diagnosed with Pierre Robin syndrome. According to the National Institutes of Health, the rare condition occurs in about 1 per 8,500 births.

Children born with this condition have a smaller-than-normal lower jaw and a larger-than-normal tongue for the size of the jaw. The tongue falls back in the throat and obstructs the airway, making it difficult for the child to breathe. In many cases, the child also has a cleft palate, like Knoxley.

Five days after being admitted to the Ephrata hospital, Knoxley was transferred to Penn State Health Children’s Hospital.

“His breathing was really noisy because his airflow was obstructed,” said Dr. Jeffrey Kaiser, chief of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine at the Children’s Hospital. “We kept him on his belly so that his tongue would fall forward, and his airway would remain open.”

“The doctors were amazing,” Himes said. “You could tell they really cared about Knoxley and wanted what was best for him.”

Doctors performed various tests, including a sleep study that determined Knoxley wasn’t getting enough oxygen while sleeping. They also did a bronchoscopy, which involved inserting a tiny fiber-optic camera into his airway to make sure there was no obstruction below his tongue.

A tongue-lip adhesion followed. Dr. Thomas Samson, a plastic surgeon at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, sutured the undersurface of the tip of Knoxley’s tongue to the inside of his lower lip to hold it in a more forward position. Dr. Samson also anchored the back of Knoxley’s tongue to his jawbone to pull the tongue up out of the airway.

Unfortunately, the stitches didn’t hold. Knoxley would have to undergo a mandibular distraction, a surgical procedure to lengthen a small or recessed jaw.

“About 80 percent of the kids born with Pierre Robin syndrome don’t need surgical intervention,” said Dr. Cathy Henry, the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center plastic surgeon who performed the procedure. “In those cases, the airway obstruction is relieved with positioning of the baby alone, and overtime the lower jaw catches up to the upper jaw. At that point, the baby outgrows the airway obstruction.” Knoxley was one of the babies for whom positioning did not work.

To lengthen Knoxley’s jawbone, Henry cut it and inserted distraction devices. Twice a day, pins attached to the distraction devices were turned, gradually pulling the two ends of the bone apart and allowing new bone to form between the two ends. The team turned the pins for about one week, and Knoxley’s jaw lengthened.

“He did amazingly well,” Henry said. “Four days after having surgery, we were able to remove his breathing tube, and he could breathe well regardless of position.”

Himes said that the days following the surgery were some of the hardest for her. “It was tough seeing him struggle and in pain,” she said. “But the doctors kept reassuring me that what he was going through was normal, and that he would get through it. As soon as the breathing tube was removed, he made a complete turnaround.”

On Feb. 1, 45 days after he was born, Knoxley came home.

Kaiser said that mandibular distraction is the procedure that he finds most rewarding to do. “To be able to fix this when a child is a newborn is incredible. The child begins with a small chin that is progressively moved forward.”

Knoxley continues to make progress, Himes said. Within two weeks of being home, he didn’t need a feeding tube and was able to take a bottle. His next surgery to remove the distraction devices is scheduled for April 2. “The new bone is essentially scar tissue that has to harden,” Henry said.

Doctors plan to repair Knoxley’s cleft palate when he is between 12 and 18 months.

“When you repair a cleft palate, you are making the airway smaller,” Henry said. “In any child where there’s a concern about the airway, we give them time to grow and get a little bit bigger and stronger before doing that surgery.”

A multidisciplinary team at the Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic, which includes Henry, will continue to monitor Knoxley as he grows. The clinic, the first multidisciplinary cleft palate clinic in the country, is completely client-centered, Henry said. “Every specialist at our clinic sees the patient during the visit and meets later to discuss the case.”

The team includes a plastic surgeon, orthodontist, pediatrician, pediatric dentist, speech pathologist, feeding specialist, social worker, ear, nose and throat doctor and audiologist.

“We are so glad to have him home and very thankful to all of the doctors and nurses who took care of him,” Himes said. “They were incredible.”

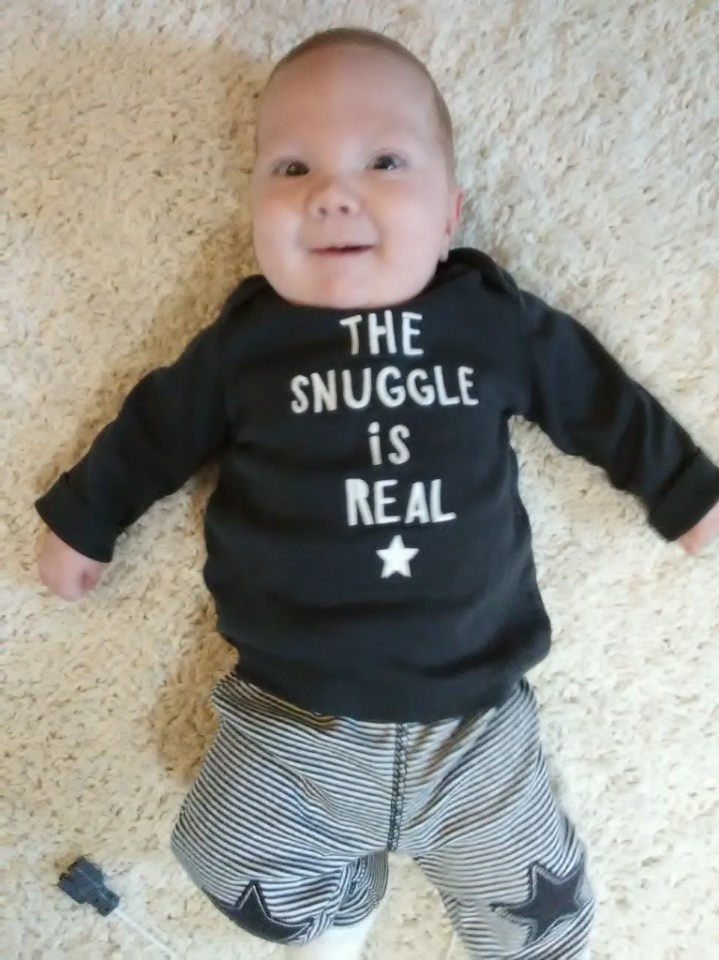

Knoxley went home 45 days after he was born.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.