Heartfelt reminders: A young man’s cancer battle inspires a new legacy gift

Dylan Gilbert stole his mother’s heart the moment she laid eyes on him.

“It was love at first sight,” said Wendy Gilbert, recalling the rough, 14-hour labor that ended with a cesarean section. “He was a chunky baby, adorable. He was my boy.”

On Nov. 22, 2021, just shy of celebrating her son’s 20th birthday, Wendy Gilbert’s heart broke as she kissed her boy’s cheek one last time.

“Dylan was more than a son to us. He was our world,” Gilbert said. “I know he wouldn’t want me to be sad, but everything just makes me cry, knowing he’s not going to be here again.”

Dylan, who was Ronald and Wendy Gilbert’s only child, was diagnosed in October 2020 with a rare, cancerous mediastinal germ cell tumor. Imaging ordered due to a bad cough showed a mass on his chest.

The 19-year-old Chambersburg teen passed away 13 months later, after a fight that included four rounds of chemotherapy, two rounds of high-dose chemotherapy and three high dose-chemotherapy treatments with stem cell transplants.

He left behind a wound that will never heal, but also a gift that helps his parents through their grief – a project of his own that will help future families faced with the unthinkable.

Heartfelt reminders

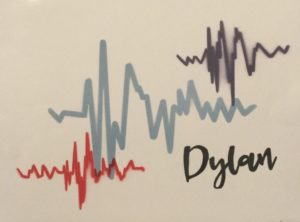

Wendy and Ronald Gilbert smile through tears as they hold a tangible reminder of their son’s heart in their hands – a visual representation of Dylan’s heartbeat – created as a legacy gift at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center.

Legacy gifts are given to the family as a remembrance after a child passes away, and the child often has a voice in deciding what it will be, said Alexis Lombardo, board-certified art therapist.

“Dylan came up with the idea of our three heartbeats – his, mine and his dad’s – spray painted in different colors,” Wendy explained. “He was always a kid who thought outside the box.”

A unique legacy gift includes a spray-painted visual representation of Dylan Gilbert’s heartbeat along with the heartbeats of his parents.

When making a casted handprint through the Child Life Program, Dylan wondered if the same could be made of his heartbeat.

“That’s when the idea for a 3D model was born,” Lombardo said. In a collaborative effort, Lombardo took an image of Dylan’s heartbeat to Mike Cote, a multimedia specialist at Harrell Health Sciences Library, who created a reverse, 3D print of the heartbeat.

They cast the 3D print in silicone, leaving only the negative space of the heartbeat behind. Lombardo mixed resin, adding a light blue color per Dylan’s preferences, into the mold and let it harden. After three days, she removed the 3D model from the silicone mold – an innovative blend of art, technology and love.

“It’s his actual heartbeat, something they can hold in their hands, and something they will always have to remember him and the memories they cherish,” Lombardo said.

The prototype of Dylan’s heartbeat lives on, as he gave permission to use it as the model for a new legacy gift option for grieving families.

To his parents, that’s a fitting legacy for a guy who loved helping others.

At his job at the local grocery store in Chambersburg, he was known for his bright smile and attentive service. A “quirky” young man, by his mom’s definition, Dylan loved to make people laugh, especially the children at his mom’s in-home daycare. He also loved roasted marshmallows, Boy Scout camp and his Australian shepherd puppy, Mocha. He had just taught her to fetch.

A fighter by nature, Dylan was also fiercely loyal. One of his favorite activities was the U.S. Navy Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corp., which he had joined while a student at Chambersburg Area Senior High School. He took pride in wearing his uniform, keeping his shoes shined and making plans to join the military upon graduation, his mother said.

Hearing loss discovered at age 16 put an end to those plans, but showed his parents how hard he had fought to compensate all through school.

They didn’t know then that the hardest battle was on the horizon.

Change of plans

Last June, Dylan had surgery to remove the tumor and enjoyed a two-month reprieve before the cancer returned, this time in his liver, lungs and bones.

“Honestly, I didn’t want to believe it,” Wendy said. “Dylan always had so much hope. He’d ask, ‘Mama, why can’t they cure me?’”

Dylan Gilbert was best buddies with his dog, Mocha.

Like any mother whose child’s tears stain her face too, Wendy struggled to give an answer and, in the end, couldn’t bring herself to have a “last” conversation with her son. He understood the cancer had spread, but she never wanted to take away his hope.

“He didn’t want to know how much time he had left,” his mother said. “I think he would have given up if he had known.”

In November, Dylan returned home from the hospital, chemotherapy abandoned due to too much pain. Mocha brought a ball and laid it on a chair near Dylan, eyeing him expectantly. He was too weak to throw. Mocha laid down by her buddy and rarely left his side.

The Gilberts’ cousin organized a drive-by parade, and Dylan dug deep for energy to walk to the front door to see his friends and the state police and community fire trucks pass by.

“That was the last time we saw his smile,” Wendy said.

Dylan passed away the next day, three days before Thanksgiving. A memorial service was held on Dec. 11, his 20th birthday. More than 200 people turned out to celebrate his life.

Finding a new rhythm

It’s impossible to say how much the care and support from staff at Penn State Health Children’s Hospital, Four Diamonds and Ronald McDonald House means to parents who walk a foreign road between life and death, the Gilberts said.

As they travel back without their child, any keepsake becomes priceless.

“Sometimes, it seems like Dylan is still with us because of that heartbeat,” Ronald said, and Wendy nods.

“Dylan will always have my heart,” she said, through tears.

And she will always have a part of his.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.