Penn State mounts broad attack on opioid addiction in Pennsylvania

A startling 13 to 16 people die each day in Pennsylvania due to opioid overdose, among the more than 70,000 Americans who succumbed to the epidemic in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That gives Pennsylvania the dubious distinction of being ranked near the top of opioid-related death rates in the U.S.

“Alcoholism is still the most common substance use disorder, but it has been eclipsed by the opioid crisis because people are dying,” says Dr. Sarah Kawasaki, medical director of the Advancement and Recovery opioid addiction treatment program at Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute. “It’s killing people in the prime of their lives. Children are without parents. The number of deaths is what makes this epidemic so important.”

That’s why the clinicians, researchers and administrators with Penn State Health and Penn State College of Medicine have united to fight the opioid crisis. Their weapons are evidence-based clinical treatment, research and education, and they are aiming at every phase of the problem ― from pre-addiction through treatment and recovery.

“We feel a sense of urgency. Opioid use disorder is a multifaceted issue that needs to be addressed at every single level,” says Sue Grigson, director of the Penn State Addiction Center for Translation based on the College of Medicine’s Hershey campus. “Fortunately, we have the right individuals and expertise to do that, and we’re using grants as vehicles to help us.”

The grants include a $1.5 million clinical grant, awarded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in November to, in part, help fund Project ECHO–an effort to enable doctors in widespread Pennsylvania counties to connect with experts in opioid addiction. Via teleconferencing, they have access to education and assistance with difficult cases.

Grigson also expects to hear this month whether the center will receive two additional grants totaling more than $100 million, which would expand referral services, educational outreach, translational research, screening and prevention projects, and new treatment methods. Founded just over a year ago, the center has wasted no time building a broad plan of attack.

See photos of the Fourth Annual Penn State Addiction Symposium on Flickr.

“Penn State Health now has a treatment program that served more than 600 patients in its first year,” says Kawasaki. “We have emergency room and inpatient psychiatric protocols to start patients with opioid use disorder on medication-assisted treatment programs upon admission. And we have a genuine interest across the university in starting addiction fellowships and other programs.”

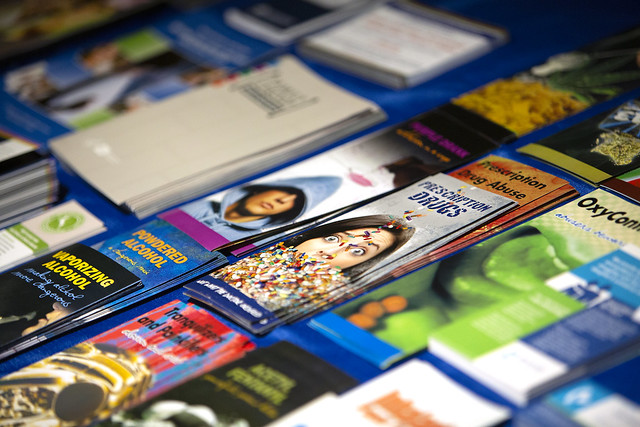

The center’s education efforts include addiction prevention sessions in Pennsylvania schools. Physicians are also being educated via Project ECHO and the Addiction Center for Translation’s annual Penn State Addiction Symposium. The 4th annual meeting took place on Nov. 28, 2018, bringing Pennsylvania medical students, clinicians, researchers, policymakers and public health experts together in Hershey to share their latest progress in the fight against opioid addiction.

“It used to be that if you had chronic back pain or migraines, the answer was opioids,” says Dr. Alexis Reedy-Cooper, a family medicine physician and assistant professor in the Family and Community Medicine Department in the College of Medicine. “Now, that’s not necessarily the answer. Primary care providers have had to learn to ask questions to appropriately identify someone with addiction. As a profession, we are learning to think about other options for managing chronic pain and take a look at our prescribing practices.”

The Addiction Center for Translation’s current clinical endeavors include a new hub-and-spoke design for a medication-assisted treatment program that provides revolutionary care access for Pennsylvania patients. The treatment escalation network allows primary care physicians to refer patients who need extra support to a more specialized, intensive recovery program.

Yuval Silberman, third from right, assistant professor in the Department of Neural and Behavioral Sciences at Penn State College of Medicine, answers a question during a discussion session at the Addiction Symposium.

“Some people think that people who are addicted are bad or that they did something wrong,” says Reedy-Cooper, who often sees patients early in the addiction process who may not even know they are addicted. “But it’s not about that—it’s like a chronic disease, something affecting their health, and as physicians we have to find ways to identify and address that with as much compassion and expertise as we can.”

Reedy-Cooper contributes to the College of Medicine’s physician education efforts, giving lectures to other doctors on screening tools and the appropriate referral process for patients who need extra help.

Kawasaki assists with the Addiction Center for Translation’s research initiatives in an effort to close the gap between bench science, clinical research and patient care. In-progress research includes studies on mobile technology to monitor treatment and recovery, a headband tool that measures brain waves to help predict relapse, a genetic screening test to identify patients at high risk of dependency, a protocol to replace opioids with more benign pain medications for new mothers and more.

“What’s unique about our center is that translational piece,” says Grigson, who is also the interim chair of neural and behavioral sciences at the College of Medicine. “We’re bringing our basic and clinical scientists together to work on grants and learn from one another. Because of that, Penn State is poised to move the bar quite a bit in the understanding and treatment of opioid use disorder and addiction.”

Researchers share their latest findings during a poster session at the Addiction Center for Translation’s 4th Annual Penn State Addiction Symposium.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.