‘Guardian of the Genome’ and the ‘WASp’ team up to repair DNA damage

DNA replication and repair happens thousands of times a day in the human body and most of the time, people don’t notice when things go wrong thanks to the work of Replication protein A (RPA), the ‘guardian of the genome.’ Scientists previously believed this protein ‘hero’ responsible for repairing damaged DNA in human cells worked alone, but a new study by Penn State College of Medicine researchers showed that RPA works with an ally called the WAS protein (WASp) to ‘save the day’ and prevent potential cancers from developing.

The researchers discovered these findings after observing that patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) — a genetic disorder that causes a deficiency of WASp — not only had suppressed immune system function, but in some cases, also developed cancer.

Dr. Yatin Vyas, professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Penn State College of Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at Penn State Health Children’s Hospital, conducted prior research which revealed that WASp functions within an apparatus that is designed to prevent cancer formation. As a result, some cancer patients had tumor cells with a WASp gene mutation. These observations led him to hypothesize that WASp might play a direct role in DNA damage repair.

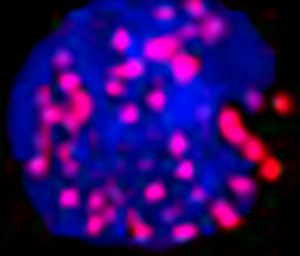

Replication protein A (RPA) forms a complex with WASp at replication forks (red) within the nucleus (blue) of a human cell during DNA replication stress.

“WAS is very rare — less than 10 out of every 1 million boys has the condition,” said Vyas, who is also the Children’s Miracle Network and Four Diamonds Endowed Chair. “Knowing that children with WAS were developing cancers and also observing WASp mutations in tumor cells of cancer patients, we decided to investigate whether WASp plays a role in DNA replication and repair.”

The researchers conducted protein-protein binding experiments with purified human WASp and RPA and discovered that WASp forms a complex with RPA. Further tests revealed that WASp ‘directs’ RPA to the site where single DNA strands are broken and need to be repaired. According to Vyas, without the complex, DNA repair happens by secondary mechanisms, which can lead to cancer. This novel function of WASp is conserved through evolution, from yeast to humans. The results of the study were published in Nature Communications.

In the future, Vyas and colleagues will continue to study how their observations about this RPA-WASp complex formation can be applied to treating cancer patients. Vyas said it is possible that gene therapy or stem cell therapy could restore WASp function and may prevent further tumor growth and spread. He also mentioned the possibility of using WASp dysfunction as a biomarker for identifying patients at risk for autoimmune diseases and cancers.

“This complex we’ve discovered plays a critical role in preventing the development of cancers during DNA replication,” said Vyas. “Translating this discovery from bench to bedside could mean that someday we have another tool for predicting and treating cancers and autoimmune diseases.”

Seong-Su Han, Kuo-Kuang Wen of Penn State College of Medicine and formerly of the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital; María García-Rubio and Andrés Aguilera of University of Seville-CSIC-University Pablo de Olavide; Marc Wold of University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; and Wojciech Niedzwiedz of the Institute of Cancer Research also contributed to this research. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the ICR Intramural Grant and Cancer Research UK Programme, the European Research Council and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation grant, the University of Iowa Dance Marathon research award, the Research Bridge Award from the Carver College of Medicine University of Iowa and endowments from the Mary Joy & Jerre Stead Foundation and from Four Diamonds and Children’s Miracle Network. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors.

Read the full manuscript in Nature Communications.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.