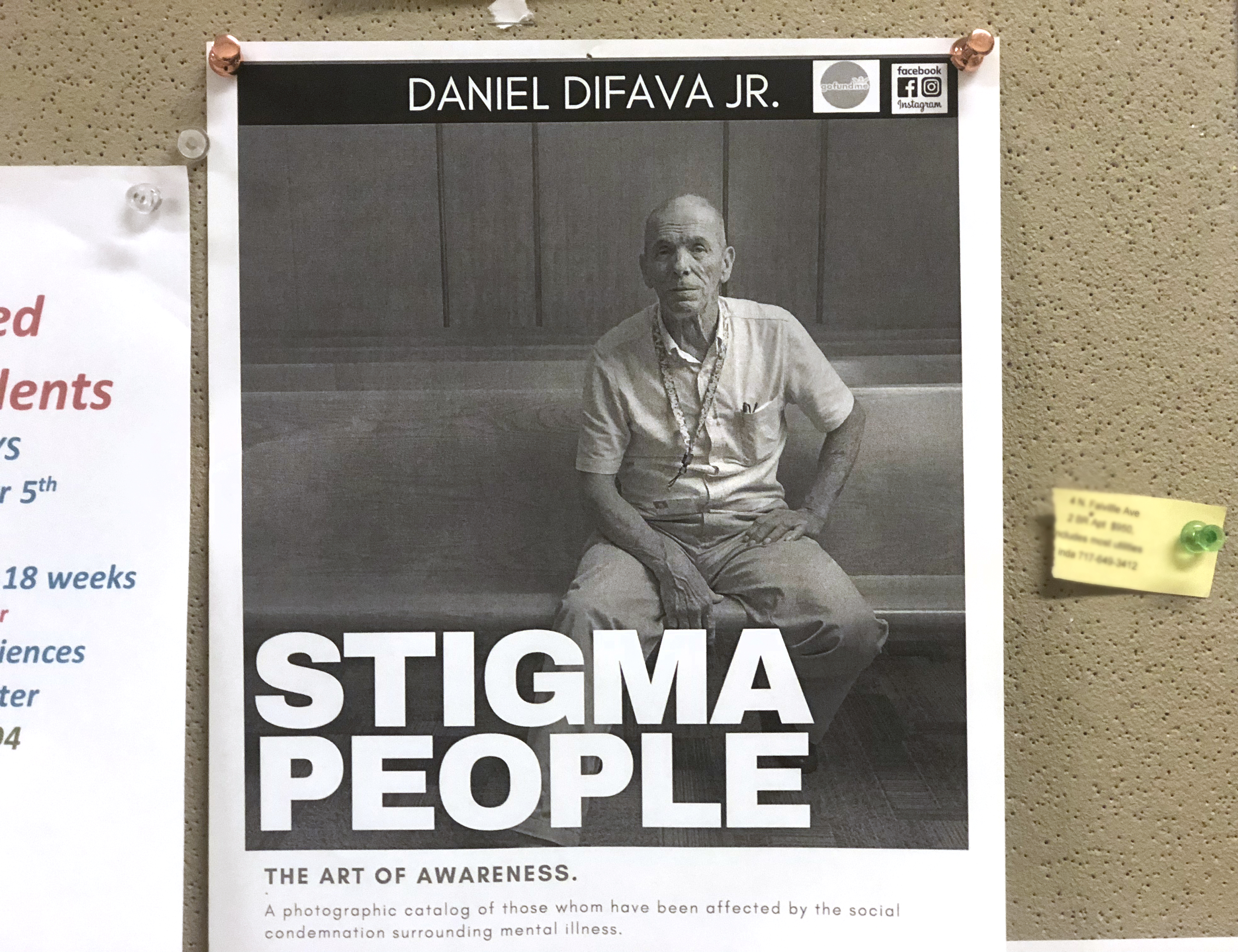

Bringing ‘Stigma People’ into focus

By Carolyn Kimmel

For 30 years, Dan DiFava Jr. wore depression like a lead blanket that at times became too heavy to carry.

“You don’t really want to die, but it’s so heavy, and you just don’t want to carry it anymore,” said the Penn State Health Environmental Health Services employee who has attempted suicide five times. “People don’t understand, so they stay away, and then you feel like no one can even help you.”

- Watch a video about Dan and his photo exhibit featuring people who have been affected by the tragedy of suicide.

DiFava traces his depression to childhood taunts about his small stature—always at least six inches shorter than his peers due to a growth hormone deficiency—and an unstable home life. Low self-esteem and loneliness were his constant companions.

When his last suicide attempt finally led to the medical help and therapy he needed, DiFava found inspiration for living in a surprising place—behind the lens of a camera.

“Photography kind of found me…you might even say it saved my life,” the 35-year-old Lebanon resident said.

Just as budding writers are told to write what they know, DiFava decided to shoot what he knew—suicide and how it looks on the faces of those who have survived it and those who have lost loved ones to its obstinate clutch.

“I met with people, told them my story, and they told me theirs. Everyone’s story is different, but there wasn’t one I didn’t connect to,” said DiFava who scoured the internet for central Pennsylvania residents who shared this common denominator. “In the beginning, it was to help me feel better about all the years I had wasted, but it’s become a lot more. With my camera in hand, I found I loved meeting these people.”

The project energized DiFava and gave him a purpose he never had.

“Stigma People”—a collection of DiFava’s photographs and stories of survivors and those who lost loved ones to suicide is on exhibit this month at the Lebanon County Council on the Arts. DiFava will be on hand for opening night from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. on Friday, Sept. 7 during Lebanon’s First Friday Art Walk.

“There are a lot of people going through it, and a lot of people who don’t know what it’s like, which fuels the cycle of loneliness,” he said. “I want to educate and honor those who struggle with suicide and its aftermath.”

Maybe it’s because mental health disorders can’t be seen in numbers on a lab test or masses on a scan that people dismiss or discredit them, said Dr. Ahmad Hameed, psychiatrist with the Penn State Medical Group ‒ Psychiatry.

They’re real enough to be seen in some pretty startling statistics, however. Every year in the U.S., 45,000 people die by suicide, and the rate has been rising slightly every year since 2000, Hameed said. “Ninety to 95 percent of the folks who commit suicide have a diagnosed or a diagnosable mental health disorder.”

Lack of awareness and hesitation to talk about mental health fuel a cycle of suffering and self-harm that’s extremely frustrating because there are effective resources available to provide support and help, Hameed said.

“We should be mindful that this is a public health issue, and we need to educate people about it,” he said. “Mental health disorders are treatable. We don’t have to lose 120 to 130 people every day.”

Andrea Sloan knows both sides of suicide—and its lasting scars. She attempted suicide as a teenager, and it was her dad—who also struggled with depression and anxiety—that got her help. Four years ago, he took his own life.

“My emotions can range daily, from anger and sadness to remorse and survivor’s guilt,” said the Etters resident whom DiFava connected with due to her participation in the South Central Pennsylvania Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Her experiences shaped her life and her career. She holds a master’s degree in mental health counseling and is earning a doctorate in counseling education.

Separate from her photo, Sloan’s 11-year-old daughter wanted to pose for her own picture—third-generation proof of suicide’s reach.

“I hope these pictures spur dialogue. The more we talk about it openly, the better,” she said.

Hershey resident Staci Wisniewski hopes to attend “Stigma People” with her niece, now a seventh grader, who was 3 when her mother checked herself out of rehab and jumped off a bridge in Maryland. Wisniewski holds a picture of her in the photograph DiFava took.

“My brother’s girlfriend had several suicide attempts, and I knew it. I should have been talking to her about, but it seemed taboo,” Wisniewski said. “Occasionally, I see some signs of her mental health behaviors in my niece.”

This time, Wisniewski won’t stay silent.

“I want her to understand that mental health can be an illness and what to do if she feels like that,” she said. “We have to be willing to have the conversation. If someone gets cancer, everybody runs to help. Mental health conditions should be the same way.”

Family members should look for warning signs—such as self-isolation, falling grades, missed work days, insomnia and personality changes—and ask a loved one about their feelings, Hameed said.

“Don’t worry if you don’t have the answers. Encourage them to go see their primary care doctor or a mental health professional,” he said. “More often than not, patients are relieved someone wants to talk about how they are doing.”

Intervention by a family member is what saved DiFava that dark day five years ago. “I can’t say for sure I’ll never feel that darkness again, but I know I’m someone I never thought I would be,” he said. “I’m a better person, a better man.”

And that lead blanket? These days DiFava has traded it in for something much lighter.

“I feel like I’m meant to carry some sort of torch for a message even beyond suicide, for humanity. People need to listen to each other and be there for each other,” he said. “When you feel inspired and you inspire others, it’s just wonderful.”

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

1-800-273-8255

“Maybe someone will come off the street that’s thinking about committing suicide,” said Dan DiFava Jr. about his upcoming gallery exhibit “Stigma People, “and they look in there and say, ‘Hey, I’m not alone in this.’” The gallery can be seen throughout September at the Lebanon Valley Council on the Arts.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.