Destination safety: teen driver education a priority at Penn State Health Children’s Hospital

By Carolyn Kimmel

Penn State Health Children’s Hospital pediatrician Dr. Erich Batra and his daughter had a special date with an important goal last fall—to drive safer and smarter.

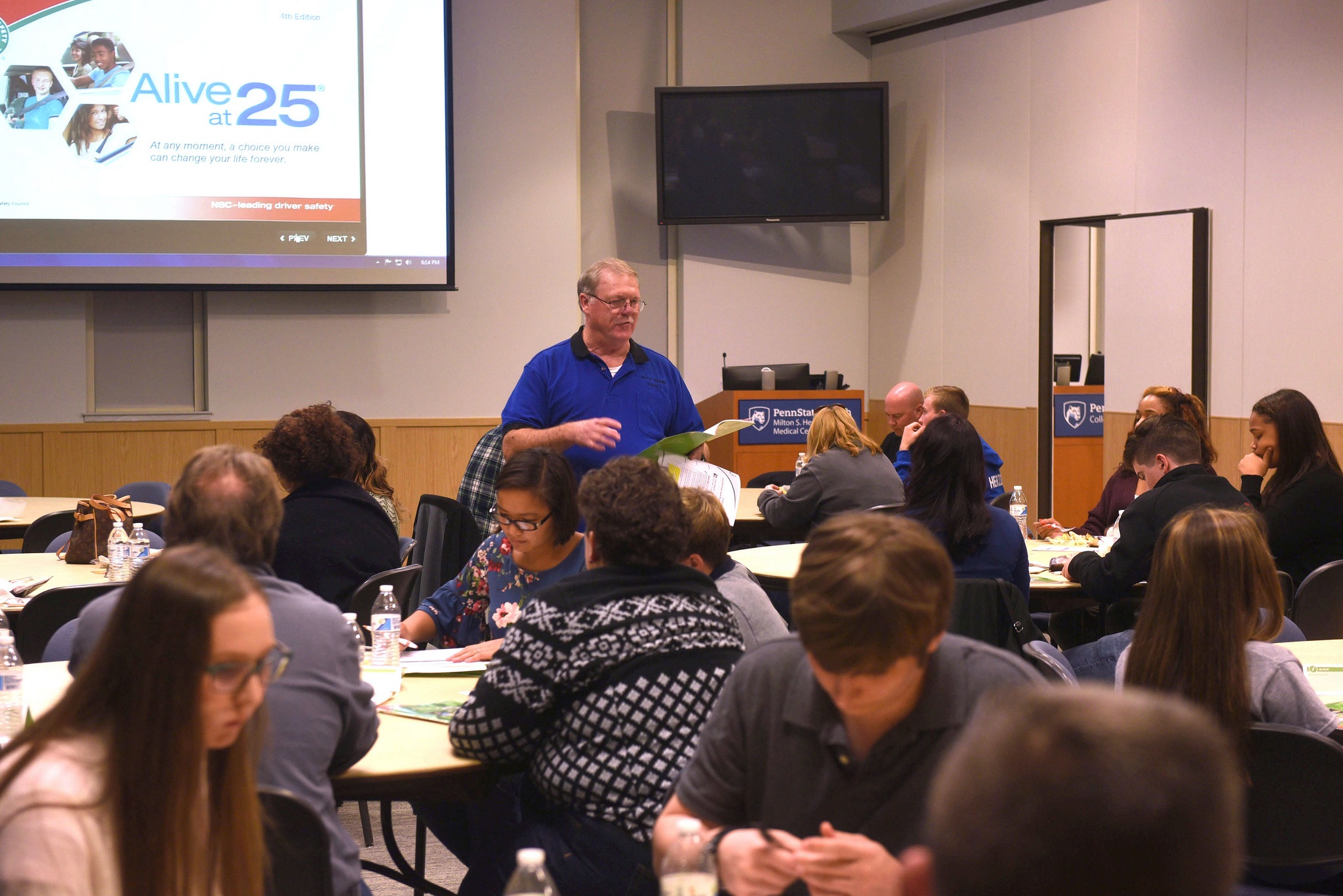

The pair were part of the first Alive at 25 driver’s awareness course presented by the Penn State Trauma Community Outreach team. Designed by the National Safety Council, the course teaches drivers age 15 to 21 and their parents strategies for keeping safe on the road and tackles decision-making and responsibility-taking.

“My daughter is a very good driver, but I felt like the course would be a good reminder for her and for myself,” Batra said. “Any opportunity we have to reinforce what good driving behavior looks like is worth it, and teens need to hear it from someone other than their parents or driving instructor.”

See more photos of the Alive at 25 course on Flickr.

Batra said his daughter, who is 17 and already has her license, didn’t particularly want to go to the course, but she knew it was important to her dad. The sacrifice paid off because she ended up winning a gift card given away by Penn State Health, he said. The course was open to Penn State Health employees and community members.

“Since we are a trauma center, the entire medical staff sees the pain and agony that some parents and their kids go through,” said Beverly Shirk, pediatric trauma coordinator at the Children’s Hospital. “It just breaks our hearts, so we are pretty passionate about education.”

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center is the only Level 1 adult and Level 1 pediatric trauma program in Pennsylvania. The designation indicates that a center provides the highest level of trauma care with all necessary specialists, equipment and every possible resource available at all times, according to Amy Bollinger, pediatric trauma and injury prevention program manager at the Children’s Hospital.

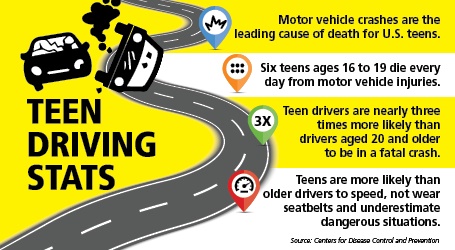

“Our trauma registry data demonstrates that the second-leading cause of pediatric trauma admissions at Penn State Health Children’s Hospital is attributed to motor vehicle collisions,” she said. “Every year, we are witness to teens whose lives have been permanently changed by car accidents.”

National statistics say approximately 30 teens are injured in motor vehicle crashes involving an inexperienced driver about every hour, and each day, seven will die in those collisions. Many of the accidents are preventable if only teens would slow down and wear their seatbelts, Shirk said.

“Forty-two percent of the teens ages 17 to 20 that we treat here after car crashes were not wearing their seatbelts, and in about half of all the teen car crash patients we treat, speeding was involved,” she said. “We know seatbelts and speeding are two areas we can really work on.”

In the interactive course, students learn through media, workbook exercises, role-playing and class discussions.

Robert Gilmer, an Alive at 25 instructor, asks participants how to stay safe in various driving situations during a group discussion.

New driver education is particularly important now when so many schools are essentially eliminating driver’s education from their curriculum, leaving parents to teach their teens on their own, Shirk said.

“The course really encourages dialogue between the parent and child around good decision-making on issues like speeding, wearing a seatbelt and cell phone use,” she said. Participant pairs watch a video that presents a driving scenario and then talk together about appropriate behavior.

Students also get a turn behind the wheel of the trauma team’s newest teaching tool, One Simple Decision. Like a video game with a steering wheel, the simulation-based program tracks and displays driving violations, including speeding, swerving, running stop signs and driving in the bike lane.

“Data suggests the use of driving simulation is effective in behavior modification with teen drivers,” Bollinger said.

The Trauma Community Outreach team plans to use the driving simulator, purchased with funding from the Association of Faculty and Friends of the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, in the community and in local high schools, she said.

Shirk applauds parents like Batra who monitor their teen’s driving even after a license is earned. Parents know firsthand how their teens are driving during the learner’s permit stage, but parents should stay involved to ensure their kids are wearing seatbelts, not driving after the state-mandated curfew of 11 p.m. and not driving a carful of friends, she said.

Cell phone use isn’t tracked in trauma hospital admissions, but it’s a huge threat to safety, Shirk said. “Teens use their phones for talking, texting, playing games and setting music in their car,” Shirk said. “We recommend putting the phone in the glovebox or even the trunk because the ‘ding’ of an incoming text is so tempting.”

That means Mom and Dad, too. Shirk said that kids watch their parents from the moment the car seat is turned around and will likely model their driving as well.

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email the Penn State College of Medicine web department.