College of Medicine students take on interpreter roles

By Jade Kelly Solovey

You’re in a foreign country, unfamiliar with the language and you suddenly are in an emergency room gravely ill. No one speaks your language. You’re frightened, confused and miming your symptoms to a doctor who is actually trying to ask about family history or medication allergies.

This scenario is common for many immigrants to the United States and the health care providers who care for them.

To address this situation, bilingual medical students attending Penn State College of Medicine can now participate in a medical interpreter training and certification program through the Health Federation of Philadelphia.

The program was the result of happenstance when Dr. Patricia Silveyra, assistant professor of pediatrics, biochemistry and molecular biology, and humanities, attended a meeting of the Latin American Medical Student Association where a group of bilingual students questioned why they couldn’t use their second language to help their patients.

“You can’t just show up and translate because you’re bilingual,” Silveyra explained. Medical interpreters require training and certifications, and they need to understand the value of cultural competency.

Because of their interest, Silveyra arranged the training for the students with the hope to increase the number of interpreters for different languages. The College’s Office for Diversity and Inclusion and the Campus Council on Diversity funded the initial program.

Among the first group of students was Colombian born Alvaro F. Vargas, Class of 2017.

“Interpretation is very complex, it’s a lot more than literally changing the words from one language to the other,” Vargas said. “It’s about how respectful you have to be with the privacy and with cultural values of different people.”

Vargas has noticed his new skills have made patients more comfortable and he is often treated like family once they realize he speaks the same language.

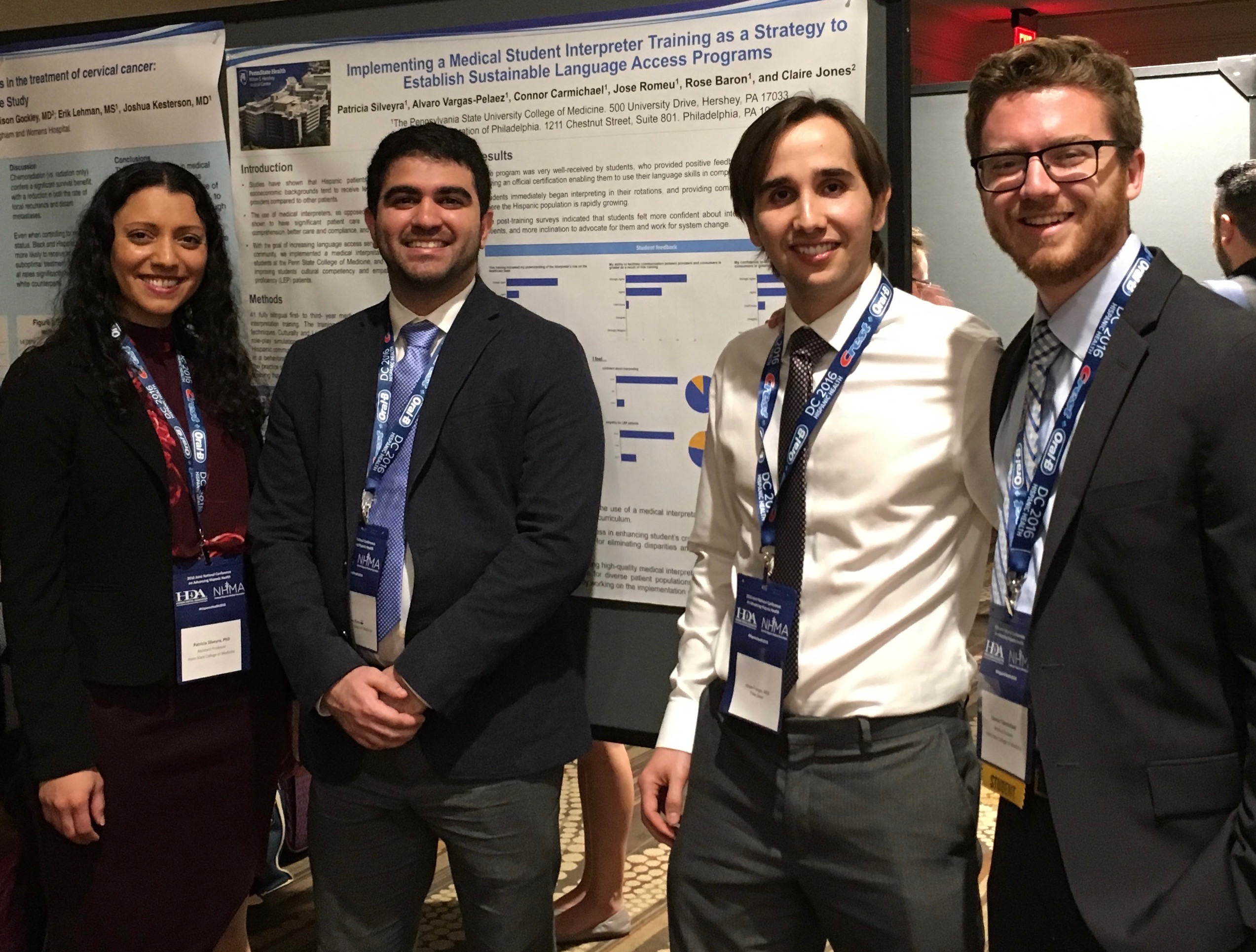

Penn State College of Medicine students take part in training to learn to become interpreters.

“Once they know you can be the advocate, not only for the medical care but also for cultural differences, they feel safer and more comfortable,” he said. “The patient is speaking directly to the physician and the physician to the patient and it flows much better.”

The training consists of 12 hours of class, plus 15-to-30 hours of practice depending on the language, followed by a certification exam.

“For the test, we try to make it as challenging as possible so that students experience those real life situations that can happen,” Silveyra said. “They need to be ready to deal with that and be uncomfortable.”

In Silveyra’s experience, patients who do not speak English may feel like they’re being judged, which can add an additional layer of sensitivity to a situation where a patient may feel embarrassed discussing the subject matter.

To date, more than 50 students have been trained and certified and the College continues to look for ways to utilize their skills in the Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center and to benefit the community. Silveyra has obtained grants from the hospital’s community relations department to sponsor interpreters’ visits to free clinics in Lebanon and Harrisburg.

The Medical Center can now utilize the students in this capacity as needed rather than hire interpreters from companies that may require a minimum time commitment. The hospital averages 550 interpretations per year.

“Considering a doctor’s visit can last only 15 minutes, it can be expensive for the Medical Center to hire an interpreter each time,” Silveyra said. “My ultimate goal is to first have more interpreters from various languages, because we have populations that come here that don’t really speak English. But my main goal is to use this training as a means to improve empathy and cultural competency in our students.”

The student interpreter program at Penn State College of Medicine has been such a success it was presented at the National Hispanic Medical Association conference. From left, Patricia Silveyra, PhD, assistant professor; Jose Carlos Romeu, Class of 2017; Alvaro Vargas-Pelaez, Class of 2017; and Connor Carmichael, Class of 2018.

Student interpreters speak Mandarin, Cantonese, French, Creole, Hindi, Vietnamese, Persian, Ukrainian, German, Korean, Arabic, Portuguese and Spanish.

Vargas continues to recruit more students and hopes to keep expanding the program.

Students who are not bilingual can participate in the training to learn how to best work with an interpreter in the future. This will help them understand the process of interpretation.

Participants who do not speak a second language can also benefit from the knowledge of cultural sensitivity.

For example, a Muslim or Arab-woman may be accompanied by her husband who remains in the room with her or she may not speak directly to the doctor.

“There are things that need to be respected culturally and we try to cover those things as well,” Silveyra said. “Interpretation is not just language; it’s also what else you need to consider when you refer to a patient that is not from here.”

The Office of Diversity and Inclusion also offers an online training called CultureVision to present topics on ethnicity, religion or country.

While the training is helpful, Silveyra believes there is no substitute for hands on learning.

“You can sit there and take whatever training you want, but the value of being in the room, serving as an interpreter and seeing it with your eyes, that is better than any online training you can take,” she said.

She believes it best to expose the students to circumstances they will likely face in their careers.

“When I first came here, I couldn’t speak much English, and I had to go into the emergency room and it was awful,” Silveyra said. The doctor tried to speak Spanish but she could not understand him.

“So just knowing a second language a little bit, doesn’t really help in those circumstances,” she said.

A simple misunderstanding can be life threatening in a medical situation. There is the potential for an allergic reaction to medication or a drug interaction if a doctor doesn’t know what medications a patient is allergic to or is currently taking.

Vargas had an experience of his own with a patient who spoke Mandarin.

“When I was on psychiatry service, we had a middle-aged woman who came to the emergency room because she was referred by her family doctor saying she was having active suicidal ideations,” he said.

Vargas used an interpreter who communicated with the patient via an iPad service.

The interpreter determined that the referring physician had confused the word for a sensation in the chest and thought the patient wanted to stab herself.

“That’s the kind of thing that can happen,” he said. “We caught it and it was only a few hours of her time, but she was so confused she didn’t know why she was going to the emergency room.”

Vargas hopes that this project will serve as a catalyst for change.

“We want the patients to make informed decisions,” he said. He it will be helpful during complex discussions regarding consent forms and risk and benefits that providers have with patients.

“It only makes sense to utilize the skills of the people who are already here,” he said.

The student interpreter project recently received a grant from Highmark to continue the training and presented their work at the National Hispanic Medical Association meeting last spring.

“I strongly believe that in order to take care of our diverse population we need strong multi-cultural skills,” Vargas said. “Being a trained interpreter has made a huge impact in the way I interpret and interact with all patients.”

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email Penn State Health Marketing & Communications.